What does Don Quixote tell us about moral decadence of American society?

The novel by Cervantes is a powerful and insightful allegory for the decadence of a ruling class and the moral order which legitimizes it.

Four and a half centuries ago, Miguel Cervantes wrote a serialized story about an elder petty noble Alonso Quijano. Quijano, on the cusp of senescence and with his head filled with airy nonsense from moralistic romances about chivalry, begins identifying as the great knight Don Quixote. He put on a rusty old set of armor and weapons, mounted his beat up old work horse Rocinante, and left his estate alongside his “trusty” old “squire”, the peasant Sancho Panza. Don Quixote told the story of Quijano’s adventures across a decadent Spanish feudal society, where the old moral, religious, and political hierarchy had lost its legitimacy in the face of a nascent capitalist economy.

Cervantes was a keen observer of the decadent nature of this society and its consequences, and the vacuity of the chivalric nobility which oversaw it. The Spain of Cervantes was a century out from the the Reconquista, where Catholic Castile and its allies spent half a millennium slowly pushing the Muslim principalities out of the peninsula. The Spain of the Reconquista was a land of brave knights who fought crusades against equally brave Andalusian nobles across the plains and the mountains of Hispania. Of course, this was a romanticization, as these knights committed all the terrible atrocities that were normal of feudal war. They sacked villages, enslaved their rivals, and butchered innocents. Yet the knights, like their Muslim rivals, nonetheless had a code which they followed even if imperfectly. Through this code, they could tell themselves and their people that they were fighting for God, justice, and the common weal. They were the Lancelots of Spain, who saved the noble damsels from infidels, brigands, and heretics. They wooed the damsels with these romantic exploits, and received fiefs for their service.

This culture had been captured in an idealized form in the great chivalric romances of the Feudal era, from the tales of Charlemagne to that of King Arthur. Their heroes were morally imperfect, as demonstrated by Lancelot’s adulterous designs on his lord’s wife Queen Guinevere. Yet even in their adulterous desire, they demonstrate their virtue as it is only their great courage, beauty, and respect for duty that they fall in love. As Engels explains in The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, adultery was the consequence of the practical realities of marriage for power and property. Aristocrats could never marry out of love, as they had to keep the fate of their homestead in mind at all times. Yet once married, they could still fall for those nobles who won their heart. He tied this reality to the prevalence of (often unconsumated) adulterous love in the Chivalric romances:

At the point where antiquity broke off its advance to sexual love, the Middle Ages took it up again: in adultery. We have already described the knightly love which gave rise to the songs of dawn. From the love which strives to break up marriage to the love which is to be its foundation there is still a long road, which chivalry never fully traversed. Even when we pass from the frivolous Latins to the virtuous Germans, we find in the Nibelungenlied that, although in her heart Kriemhild is as much in love with Siegfried as he is with her, yet when Gunther announces that he has promised her to a knight he does not name, she simply replies: “You have no need to ask me; as you bid me, so will I ever be; whom you, lord, give me as husband, him will I gladly take in troth.” It never enters her head that her love can be even considered. Gunther asks for Brunhild in marriage, and Etzel for Kriemhild, though they have never seen them. Similarly, in Gutrun, Sigebant of Ireland asks for the Norwegian Ute, whom he has never seen, Hetel of Hegelingen for Hilde of Ireland, and, finally, Siegfried of Moorland, Hartmut of Ormany and Herwig of Seeland for Gutrun, and here Gutrun’s acceptance of Herwig is for the first time voluntary. As a rule, the young prince’s bride is selected by his parents, if they are still living, or, if not, by the prince himself, with the advice of the great feudal lords, who have a weighty word to say in all these cases. Nor can it be otherwise. For the knight or baron, as for the prince of the land himself, marriage is a political act, an opportunity to increase power by new alliances; the interest of the house must be decisive, not the wishes of an individual. What chance then is there for love to have the final word in the making of a marriage?

During the time of the Reconquista, the ethos of chivalry was necessary. It was a feudal world, dominated by the hierarchy of nobility, but it was also a deeply militarized world where this noble hierarchy was defined by its ability to fight. As a class with an unassailable monopoly on force, the knights were as much a social hazard as they were a protector. A knight unchained by a chivalric code would become nothing more than a wealthy brute roaming the countryside, raping and pillaging while taking whatever he wanted from the weak. A society governed by such people would become ungovernable, and destroy the very soil which sustained it. Instead, knights had to be bound by a code which told them to protect and serve the weak, fight one another with honor, and remain loyal to their liege. Their reward would be a fief from the king, and entrance into heaven once they died (whether in battle or in their manor). Thus, we see such codes across “feudal” societies, from the aforementioned Chivalry of Europe to the Bushido of Japan to the ethea of Muslim Ghazi and Hindu Rajputs.1

Once Spain had completed the Reconquista with the fall of Granada at the end of the 15th century, this great epoch of noble warfare tapered off. The great warriors of Spain during the 16th century were the brutal and conniving conquistadors, who did not follow any ethos to speak of beyond the greed of disease, and sought wealth and glory by any means necessary.2 They did not receive fiefs from a lord who closely monitored their deeds and virtue on the battlefield, but instead lied, butchered, and plundered their way across the New World. These conquistadors fought in Mexico and Peru, not in Spain itself, but sent back massive amounts of wealth to their home country.

In such a setting, the Spanish nobility of old became a decadent class. Their function was no longer to protect the peasants on their fief, but merely to tax them and enjoy the manors and castles which their forefathers had won them. Small nobles like Alonso Quijano had enjoyed social mobility during the Reconquista, as they could gain larger fiefs through courageous action on the battlefield. Yet during the peaceful time that followed, true social mobility was largely foreclosed for anyone not willing to cross the Atlantic to the New World. They had nothing to do but sit in their manors, live off of the rent, and read the chivalric romances about their ancestors.

Cervantes saw how the ethos of this noble ruling class had become entirely decadent. It had lost the material conditions that gave it meaning and forced its adherents to find virtue within it. Rather, it became an empty husk that merely provided sanction for an increasingly degenerate ruling class. This new epoch was not defined by nobility or courage, but by privilege entirely disconnected from virtue and where political and economic self-interest had hollowed out the old moral order.

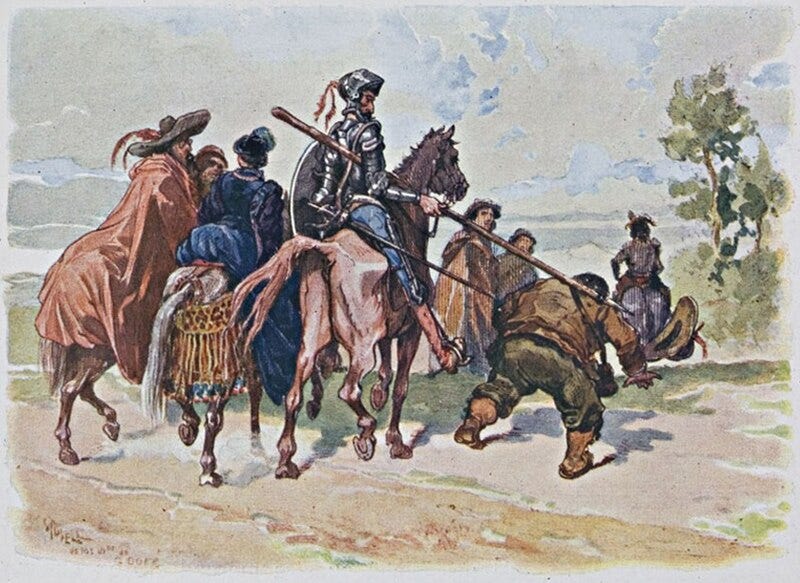

As a true believer in the old morality, Don Quixote was unable to properly interpret his surroundings. The famous example is from early in the novel, where he perceives a windmill as an ogre menacing the townspeople. While his peasant squire sees Quixote’s mistake, Quixote “valiantly” charges the “ogre” before getting his lance stuck in its “arms” and raised over the fields below. Likewise, Quixote interprets the small business of the inn as a great castle, and its bumbling low-class owner as a fellow member of the nobility. Don Quixote interprets the new nascent capitalist society emerging in Spain through his old novels. What is a windmill? It is literally capital, as a piece of property intended to convert grain cheaply and easily into flour or pump water out of the ground. Yet capital does not exist in the legendary chivalric romances he read. Profit was the last thing from the mind of their authors or the characters inhabiting them. Though inns and windmills existed in the time of the chivalric romance, they were not the center of that society. In the new Spain defined by peace and increasing prosperity, however, they became the instruments propelling society forward into the new era Quixote could not understand.

So many of the stories and subplots that constitute the narrative follow this pattern. Some new feature of the peaceful Spain gets interpreted through the lens of the old moral order of knight-errantry and treated accordingly by Don Quixote. He is a true hero, insofar as his belief in this world is defined by its good faith. He really does believe that the windmill is an ogre. Yet his actions are comic precisely because his interpretation of reality is so deeply antiquated.

Karl Marx noticed this fact about Don Quixote, writing in a footnote of Capital that “Don Quixote long ago paid the penalty for wrongly imagining that knight errantry was compatible with all economic forms of society.” Likewise, the Hungarian Marxist György Lukács noted the following:

The target of Cervantes’ satire is not enthusiasm in general, but that of Don Quixote, an enthusiasm with a defined class content, and the satire is directed against this concrete content. Hence, the particular aspect of the whole world of this novel. The unenlightened reader will laugh at Don Quixote, at his ideology and his aims, but at the same time he experiences a profound sympathy with the moral purity of his enthusiasm.

The solution to the puzzle is to be found in the question of transition due to the formation of a new class society. (Lukács 1951, 1951)

The point is that Don Quixote remained, at least in moral terms, one of the knights of old. Yet this ethos was fundamentally anachronistic, and he had become a man out of time and place.

The novel ends with two signature events. First, he and Don Quixote get manipulated by the bored upper nobility when an Aragonese Duke and Duchess decide to use him for their amusement. They play all sorts of other hijinks on the pair, and the central reason Don Quixote falls for this is that they are aristocrats who appear to treat him in accordance with the rules of chivalry. They do this for their own amusement, as they had become aware of Don Quixote and his exploits through reading the first volume. They were wealthy, privileged, and incredibly bored, and Quixote with his hapless “squire” was the perfect source of good fun.

Through this novel, Cervantes identifies and critiques the decadent nature of the Spanish Aristocracy as a whole. Broadly, we can identify three paradigmatic characters that capture the Spain of his time:

Don Quixote - as explained, Don Quixote is a true believer in the aristocratic ethos of chivalry. Yet his belief is characteristically delusional, as the ethos he believes in has no relevance to the world he inhabits. This leads him to harm those around him while trying to help. He is a noble person, and in one case, he actually does the right thing. He saves the shepherdess Marcela from those trying to hurt her, because she really was a damsel in distress. Yet this instance is the exception, and his accurate diagnosis was merely by accident. Otherwise, Don Quixote is the comic fool whose delusional but enthusiastic and genuine belief in an empty code leads him to disaster after disaster.

Sancho Panza - Sancho Panza is a peasant and a simpleton lacking much in the way of education. Where his lord believes out of madness, Panza is a victim of his own credulity and stupidity. He often doubts his master, but he is loyal and his desire to gain a fief of his own (and therefore enjoy social mobility, normally foreclosed to peasants like himself) keeps him in line. Moreover, the not-infrequent beatings Don Quixote metes out keeps him in line. He is not without his virtues, as he is tough, loyal (as mentioned), and has some practical wisdom. When he is given the fake fief at the end of the story by the Duke, he is noted as a competent and surprisingly wise lawmaker and administrator. Perhaps after a lifetime of village life there is some wisdom in the simple peasant after all, yet he still fell for the joke.

The Duke and Duchess - These characters are the true cynics of the story. They know of all the old moral ideas which motivated Don Quixote (in fact, they are fully educated in its many details), but do not believe these old moral ideas. Rather, the old moral order is a mere means for them to manipulate others around them for their own ends. Chivalry is thus instrumentalized as a source of authority, not virtue. They suffer no real consequences for their actions, either, due to their status and privilege. Through their instrumentalization of their moral code, these people have become self-aware hypocrites. Where the Dukes of old had to be great generals and brilliant governors lest they lose their land to their rivals, this new generation can rest on their laurels.

Samson, the Priest, and the Niece - At the end of the novel, Quixote’s old friend Samson endeavors to release Quixote of his madness. He is eventually successful in this task and is assisted by the priest and Quijano’s niece who burn Quixote’s Chivalric romance stories. These characters understand the source of Quixote’s madness and must cut through it somehow to return him to sanity. Not only this, they understand the falsehood of the Chivalric romances and the significance of this falsehood. Once they have succeeded in getting Quixote and Panza home, they must deal with the problem at its source by burning the books that have poisoned the elder’s mind.

There are other important and interesting characters in the story which can serve as archetypes in their own right. There is the criminal who Quixote foolishly sets free. There is the innkeeper who suffers the indignities of Quixote’s madness. There is the damsel Marcela who Quixote saves. The novel is long, and full of all the interesting types of person Cervantes saw in his own time. All these characters could be explored in their own right, yet the four described here demonstrate important archetypes in such a decadent society. There are the true believers, the loyal camp followers, the hypocritical cynics, and those who expose the decadence of our moral beliefs.

We can apply these archetypes to our own society, which I would argue is increasingly beset by decadence. If one does not believe me, only consider the constantly accruing crises and the total failure of our ruling classes to adequately address them. One common symptom of such collective decadence is hypocrisy. Political factions in our democracy are quick to identify the hypocrisy of the other side, but rarely go beyond this by identifying the structural causes underpinning it. Consider the hypocritical response to “offensive jokes” and “violent rhetoric” after the assassination of Charlie Kirk. People who only a few months ago were “bravely” standing up for the free speech to make jokes about George Floyd’s death, the suffering of migrants, or sexual assault are today clutching their pearls over spicy jokes made by liberals over the shooting of a glorified pundit. The hypocrisy is obvious to liberals and leftists after being hectored on free speech for years, but many of those making these criticisms seem to have a blissful, Quixote-like ignorance of their own contradictions. Yet it is not like the liberals are innocent of hypocrisy either. Consider the rhetorical contrast between their reaction to the immigration policies of Trump’s first term and that of Obama’s and Biden’s. Or consider the recent scandal exposed by Taylor Lorenz, where it turns out that liberal and “progressive” social media figures have been taking money from dark money groups that have contractual rights over the messages they put out.

If anything, hypocrisy in one form or another has become characteristic of both sides of the American political debate. It is a feature, not a bug, of an increasingly decadent moral order. There may be a handful of issues where some politicians have a morally consistent view (consider John McCain’s relative consistency on torture, Bernie Sanders’s relative consistency on universal health care, or Elizabeth Warren’s relative consistency on “sensible” financial regulation). Yet on most issues, the rhetoric of politicians, media pundits, social media “influencers”, and politically influential businessmen is as unprincipled as it is shrill.

Why is this the case? A part of the problem seems to be caused by issues that have defined America since its inception. To return to Don Quixote for a minute, Cervantes thought that romantic chivalry was never a particularly great or accurate moral order. In a way, it was decadent from its inception. It is not like the knights of the Reconquista did not lie, betray, rape, and pillage when it advantaged them. Rather, chivalry was always an ideal they strived towards but rarely fully embodied. America likewise has had certain issues going back to its inception, like the incredible power of the wealthy business elite, race inequality, or the complicated relationship with tribal nations. We cannot say that America became an oligarchy only recently, and the founding fathers included many of the wealthiest men in the colonies.

Yet to a certain extent, the problem also has to do with the loss of the conditions that gave the system legitimacy. Liberal politics as practiced for the past 250 years was always flawed, but like the aristocratic knights of Spain it gained legitimacy from its ability to address present needs. Abolitionism, the 8-hour workday, civil rights, and many other real problems were effectively, albeit sometimes slowly, addressed by existing liberal institutions. Regular working-class voters, small businessmen, the wealthy, and political leaders fell on either side of these debates and were able to effectively justify their positions from it and adjudicate their disputes. The moral code that upheld these institutions facilitated and justified these methods, and apparent moral and political progress returned the favor by legitimizing it. Thus, even if this system was imperfect, it seemed just in theory if not always in practice.

Yet this is increasingly not the case in America. Real problems are merely getting worse, and the moral and practical significance of these problems for people is generally dismissed, ignored, reinterpreted, or opportunistically weaponized by the political class. Health insurance and treatment alike becomes more expensive while rural hospitals close. Graduating students are told that the best opportunities come through college, but the costs of an education are skyrocketing. Instead of dealing with climate change, we are mining more coal. A government that includes a supposed health nut like Robert F Kennedy Jr. deregulates the chemicals that poison us and our environment. The price of housing is skyrocketing, and the only hope for those without homes is that an economic catastrophe makes them affordable once more.

More importantly, addressing these problems is impeded by the very institutions justified by that liberal moral order. We cannot deal with climate change by just implementing a mass ecological industrial policy because the logic of liberal capitalism prohibits too much government meddling in the market. Thus, China which has no such constraint has massively overtaken America when it comes to producing wind turbines, solar panels, electrical vehicles, and public transit. On public transit, the “ethos” of the car owner and their independence as an individual is weaponized as a barrier against public transport while we’re stuck in traffic in increasingly over-crowded highways. Compare this to Europe, China, and Japan where extensive public transit networks have been built out. Homeowners are incentivized to vote for the very policies that price their children out of their hometown so that their real estate can appreciate in value. Compare this to the post-war Social Democracies in Europe which kept housing cheap by building it themselves, or countries like China where they have excess housing. Consider the rise of money in politics after Citizens United as money is now “speech”, and speech must be absolutely unconstrained (unless, apparently, we are saying salty things on social media). Some of these issues go back generations, but they have only gotten worse over time.

There are deep, systemic issues underpinning these issues. Different political factions take opportunistic positions on these issues as they struggle to win power over others. None of these factions have the capacity or wherewithal to solve the problems, and just as importantly they usually lack a real incentive to do so either.

In the face of such conditions, some become like Don Quixote by doubling down on liberalism, the constitutional order, “norms,” decency, the church, the military, the law, the police, and the other values, ideals, and institutions that give our society both order and moral legitimacy. They become indignant at any perceived sleight against the ideals of the society and remain committed to their ideals however frequently they fail. We can think of the enthusiastic progressives, fanatic liberals, and committed conservatives who see their partisan position as a kind of moral calling.

Others are like Sancho Panza in how they recognize the imperfection of the system but continue to embrace it, perhaps out of a hope that they get their island fief at the end of the tale, or out of loyalty and faith in their leaders (or, more likely, some combination of both). They often have practical knowledge that gets them by but are generally not intellectually curious enough to explore systemic problems in any serious way. This represents that large sum of people who are not passionate believers in the system and do not care much for politics and religion but continue to trust their leaders.

Some are like the hypocritical Duke and Duchess who recognize the absurdity of the old values but benefit from them anyways. This may be the smallest group, but is still very diverse and visible. Think of America’s social media industrialists who decry racism, embrace DEI, and throw money at democrats one year and embrace race hate, reject DEI, and throw money at Republicans the next year. Think of the mega-corporations that do the same but with less fanfare. Think of the media talking heads who become wealthy off of sophistry and incendiary rhetoric. Think of the political consultancy class that sells their advice to the highest bidder. Think of the lobbyists who sell access to the highest bidder. Think of the university administrators who treat the academy as a cash cow by chasing metrics while celebrating abstract ideas of “free enquiry”. Even think of the petty internet ideologues who farm drama and sell theories they neither understand nor believe in.

A small number are like Samson and the priest by recognizing the problem and trying to guide others away from it. They are those who accurately diagnose existing conditions and do their best to inform people what’s going on. They are few in number, and many who might look similar to this type are actually closer to the Duke and Duchess in practice. After all, it is hard to tell the difference between one who genuinely knows what’s going on, a Quixotic figure who thinks they do, and a figure who knowingly sells false solutions. The limitation these figures have in our own context, however, is they can only dispell these illusions on an individual level. They cannot address the systemic rot by fixing our institutions and can only help the individual understand their situation. After all, the institutions may well be beyond repair.

The use of Don Quixote as a grand allegory for social decadence has its limits, of course. Cervantes was, after all, not satirizing aristocratic society as a whole but only its attachment to silly romantic legends. Nor did he have a theoretically precise diagnosis of the problems with aristocratic society, something which would require the further intellectual development of philosophy and social theory. Nor did he ever criticize the aristocracy specifically. After all, much of his audience were wealthy aristocrats like the Duke and Duchess, and in a way they were a satire of his audience who had so enjoyed the antics of the first volume that most wanted a second. He did not want to insult his wealthiest customers, as Cervantes was an astute early novelist. Yet his diagnosis, despite its narrowness, was correct. Spain and its ruling class would continue down the path of decadence, never able to right its course. This Spain slowly died with the horrors of Napoleon’s invasion, the independence of its wealthiest colonies like Mexico and Peru, the reactionary Carlist wars, the seizure of most of its remaining colonies by the United States, and the brutal Rif Revolt in North Africa.3 Eventually, that system collapsed into a new epoch of modern Republicanism, Socialism, and Fascism.

Quixote is a comic character because of the anachronism of his beliefs, but he can also be an inspiration through his commitment and enthusiasm for a disappearing code. The power of Don Quixote as an allegory for naively seeking justice in unjust times has been taken up before. The Zapatista’s spokesman Subcommandante Marcos took on Quixote as a symbol of fighting for values in a world that does not correspond to them. He was fighting to preserve the ideals of the Mexican revolution and the indigenous ejido system it spawned in the face of neoliberalism. Quixote was a lazy noble turned knight-errant, and Marcos was a university professor turned jungle revolutionary. Like Quixote, Marcos’s effort failed to restore these values beyond the hinterlands of Eastern Chiapas.

We too can see ourselves in the story and how we take up the roles of these characters at various points. We too are living in a society which is losing its bearings and finds its moral ideals without legitimacy. And like Quixote and Panza before us, there’s not much for us to do with that right now except to lose our illusions and see the world for what it is.

Two points of clarity - first, the category of feudalism is deeply contested in academia, and many Medieval historians have critiqued it as a later reconstruction. Yet there are shared features of the Aristocratic agrarian societies across the globe. Second, Bushido as we know it today was not codified during the great epoch of samurai warfare, but during the later peaceful Edo period. Yet it was grounded in the robust traditions and moral codes of the samurai that preceded it.

As Cortez once allegedly told the last Aztec Tlatoani, “I and my companions suffer from a disease of the heart which can be cured only with gold.”

The Rif War was a brutal insurrection in the tiny Spanish colony in Morocco. Despite the small size of the colony, the indigenous Rif Berbers managed to decisively defeat and smash a much larger Spanish army while suffering few casualties themselves. It would further radicalize the working class against the state on the left and lead to the rise of fascist generals like Francisco Franco on the right.