How we ought to respond to automation by shortening the working day

During the rapid automation of the 19th century, Karl Marx noticed the obvious solution - shortening the working day.

With the advent of LLM chatbots and other modern forms of “artificial intelligence”, there has been considerable anxiety about the future of the labor market and the economy as a whole. These so-called “artificial intelligence” programs are pretty unreliable, but some businesses have been replacing workers with them. Even though the results are less than stellar, they are sold on it because it’s cheaper than paying employees. The effect of chatbots on the labor market have not been particularly bad yet, and the whole AI space stinks of a bubble that will pop hard in the next few weeks or months. Yet other new advances in robotics and other forms of labor-saving “efficiency” have made many workers redundant. As factories need fewer workers to manufacture more cars, combine harvesters, and canned sardines, and as our resource extraction industries become more labor efficient, we’ll see more unemployed workers. This will only drive social conflict and economic collapse, as businesses are unable to find customers and as workers will be unable to afford necessities. Many have been asking what we are to do in the face of this radically new problem. Yet it may not be so new after all, and Karl Marx already gave the worker’s movement the solution and its proof over one hundred and fifty years ago - we must shorten the working day.

At face value, it seems intuitive that automation ought to make the burdens of the worker easier. It reduces the amount they have to do to achieve the same outcome. Yet in reality, employers tend to work their workers fewer hours and if necessary lay off now-redundant workers. If it takes 100 workers 100 each hours to make 100 cars, and if a new piece of machinery allows the same number of workers to make 200 cars in that amount of time, the car manufacturer can just produce 100 cars with half as many workers. It’s unlikely the market will be able to absorb 100 extra cars, but the car manufacturer also has no incentive to let their workers work half as long. Naturally, throwing a bunch of workers out of the job is bad for everyone except the employers, as it makes the labor market more competitive. Business revels in more competitive labor market, as they can pay their workers even less without them quitting. The fired workers on the other hand get evicted, and even those who keep their jobs struggle to find enough to pay the bills. It turns out that “trickle down economics” really meant “downward mobility for most.”

What to do in the face of this seemingly unprecedented level of automation? Should we panic with the recognition that our economic future is totally hopeless? Should we downgrade to the “van life” while driving across the country seeking out temporary employment at various Amazon warehouses? And what ought the businesses do when half their customers can no longer afford their AI-manufactured slop?

Some have suggested that the solution to automation is a “universal basic income”, or a dividend for all from the overall profits of society. Taxes would rise on the owners of capital (and maybe those who still have jobs), and the money from these taxes will finance everyone. Every citizen will receive the same direct deposit in their bank account or mailbox every month. The thinking goes that this will grant the jobless masses a little bit of earning power to live off while capitalist firms can continue to find customers. The unemployed will even be able to find self-employment by using their UBI as capital (and they will be able to find customers when others use their UBI to consume). Best case scenario is that some might even be able to eke out a marginal living as artists and small businesspeople by selling trinkets online, although the worst case scenario is they get sucked into “multi-level marketing” (or, as we call it by its proper name, a pyramid scheme). Yet at least everyone can get their basic necessities met despite job losses from automation.

The advantage of a UBI scheme is twofold. First, unlike welfare benefits that only go to the unemployed and underemployed, a UBI is a universal provision meaning everyone benefits (even the wealthy). Welfare benefits, the thinking goes, creates antagonism between the jobless who get benefits and workers who don’t. Even if the cost of welfare is only a marginal, it undermines the political popularity of the idea among those with jobs. This conflict will serve as rhetorical fuel for fiscal conservatives trying to eliminate benefits. Many workers resent the “lazy moochers” enough to vote for the economic conservatives that screw them over just to deprive the “welfare queens”. By making it universal, you ensure that even those with jobs have an incentive to keep it in place. Second, since it is guaranteed, it will ensure that the difficult job market won’t constrain the demand for consumer goods. People will still be able to afford basic housing, food, and utilities even if there aren’t enough jobs for them. This will keep the capitalist economy chugging along.

Yet using a UBI as a solution to job losses from automation also has some odd outcomes. It means that a smaller number of people than ever are working long hours to live a decent life while everyone else is condemned to life off of whatever scraps of the social surplus that the state decides to share. Those with jobs will live better than before as they will benefit from a UBI (unless they’re in a higher tax bracket) but will still work long hours and not spend much time with their family. Those without jobs will struggle to find any career options if they really do want to work and be productive. As everyone from Aristotle to Aquinas to Adam Smith to Karl Marx to Camus will tell you, people find meaning through their good works. Maybe some are satisfied by a passive bohemian life of mere consumption, but many will be driven to a kind of existential depression. Moreover, learning and mastering a skill that is useful and valued by society leads them to “touch grass” and spend time with members of their community. Yet those consigned to live off of UBI for the rest of their lives and can’t find some in-demand craft to pursue don’t have option. They might simply be forced to a kind of techno-bohemian existence, where their meager UBI is used to keep them fed and online while they have little social life beyond their own four walls.

Alternatively, we can realize that this new wave of automation is not unprecedented and that there is a historically validated solution to it. In reality, the constant push for labor automation defined the industrial revolution, and led to constant waves of layoffs. Eventually, the high levels of unemployment motivated a new social movement centered on shortening the working day. This movement realized that those with jobs were subjected to intolerably long working hours while those without jobs were subjected to poverty and meaninglessness. By organizing around the 10-hour and then 8-hour work-day limit, the working class was able to unite those with jobs with the jobless. By imposing a shorter working day, the working class forced employers to hire more workers to meet demand. It reduced profit margins, yes, but only because it converted profits into wages. Eventually, this movement would succeed across much of the world gifting us with the weekend, guaranteed lunch breaks, and the 40 hour workweek.

One of the primary advocates for shortening the working day was Karl Marx, and he provided the theoretical justification for this policy in his Capital and elsewhere. He argued that if workers fought to reduce the working day proportionate to gains in productivity, they could spread employment to the unemployed while also ensuring workers have more free time. For this reason, he presented the struggle to reduce the working week to be a noble and just cause, using the kind of moral language he usually avoided. He described the movement in this way:

It must be acknowledged that our labourer comes out of the process of production other than he entered. In the market he stood as owner of the commodity “labour-power” face to face with other owners of commodities, dealer against dealer. The contract by which he sold to the capitalist his labour-power proved, so to say, in black and white that he disposed of himself freely. The bargain concluded, it is discovered that he was no “free agent,” that the time for which he is free to sell his labour-power is the time for which he is forced to sell it, [163] that in fact the vampire will not lose its hold on him “so long as there is a muscle, a nerve, a drop of blood to be exploited.” [164] For “protection” against “the serpent of their agonies,” the labourers must put their heads together, and, as a class, compel the passing of a law, an all-powerful social barrier that shall prevent the very workers from selling, by voluntary contract with capital, themselves and their families into slavery and death. [165] In place of the pompous catalogue of the “inalienable rights of man” comes the modest Magna Charta of a legally limited working-day, which shall make clear “when the time which the worker sells is ended, and when his own begins.” Quantum mutatus ab illo!

Marx challenged those 19th century theorists like Nassau Senior who argued that shortening the working day from 11 to 10 hours would eliminate the profit margins of capitalist firms, as these firms only profited from the “last hour” of work. As Senior argued (as quoted by Marx):

“Under the present law, no mill in which persons under 18 years of age are employed, ... can be worked more than 11½ hours a day, that is, 12 hours for 5 days in the week, and nine on Saturday.

“Now the following analysis (!) will show that in a mill so worked, the whole net profit is derived from the last hour. I will suppose a manufacturer to invest £100,000: — £80,000 in his mill and machinery, and £20,000 in raw material and wages. The annual return of that mill, supposing the capital to be turned once a year, and gross profits to be 15 per cent., ought to be goods worth £115,000.... Of this £115,000, each of the twenty-three half-hours of work produces 5-115ths or one twenty-third. Of these 23-23rds (constituting the whole £115,000) twenty, that is to say £100,000 out of the £115,000, simply replace the capital; — one twenty-third (or £5,000 out of the £115,000) makes up for the deterioration of the mill and machinery. The remaining 2-23rds, that is, the last two of the twenty-three half-hours of every day, produce the net profit of 10 per cent. If, therefore (prices remaining the same), the factory could be kept at work thirteen hours instead of eleven and a half, with an addition of about £2,600 to the circulating capital, the net profit would be more than doubled. On the other hand, if the hours of working were reduced by one hour per day (prices remaining the same), the net profit would be destroyed — if they were reduced by one hour and a half, even the gross profit would be destroyed.”

In other words, as profit margins are so tight, the reduction of work by one hour today would prevent businesses from making any money, and anything more than that would put businesses out of business. Reducing the working day by 10% would reduce the revenue before expenses by 10% too, and if the profit margins are 10% this means no more profit margin. Yet Marx dismisses this argument as “all bosh” because it doesn’t consider the fact that the expenses of 10 hours of work are also less than the expenses of 11 hours of work! On the contrary, every hour of work includes some fraction going to expenses for materials and machines, some fraction going to wages, and some fraction going to surplus value (surplus value being the source of profit, investor dividends, rent, and interest on loans).

It is true that the price of labor will go up with a shorter working day, because their cost of living remains the same and because the bargaining power of workers goes up when unemployment goes down. Workers still need to pay as much for rent, food, and health care, meaning that their hourly wages will increase, and there are more jobs out there for the same number of workers. This means that expenses won’t drop as much as revenue drops. Yet all that will happen is a redistribution of some of the profits to the workers.

One might ask why the shorter working day means more jobs. This is because employers still face a competitive pressure to pay for any expenses on machinery and buildings. Every firm is incentivized to “use up” their machinery as quickly as possible, because machines only depreciate in value over time (as anyone who has bought a $50,000 pickup truck can tell you). They might be the best machines this year, but next year there will be more efficient machines, and the same machines you bought last year can be purchased more cheaply. Also, mere age takes its toll, as corrosion and other damage might be slow but still noticeable. Thus, it makes more financial sense for businesses to keep the machine working for as many hours a day as possible. Some industries don’t work on these terms like retail, as nobody is out buying trousers at 3 AM. Yet a factory with modern lighting can keep as many shifts as it finds people willing to work. There are plenty of smaller businesses like fast food chains, gas stations, and diners that remain open 24/7 to feed those night shifts. The shorter working day means that factories will have to distribute the same number of work hours among a greater number of people. Imagine a factory requires 2,700 work hours a day to use its machinery as efficiently as possible. A 10 hour workday would require 270 workers working around the day, while a 9 hour workday would require 300 workers working around the day. Thus, the shorter work-day means more jobs for all.

Of course, this does mean a reduction in overall profits. Yet the automation of work is a productivity gain which increases profits. Shortening the working day doesn’t eliminate profit, it merely changes who benefits from automation. Marx argued that revenue is split between “constant capital” (or spending on resources, machinery, buildings, raw materials, and so on), “variable capital” (or spending on wages), and surplus value which is profit. This surplus value is created by the working class, which is never paid the full value of its output for the employer. What a reduction of the working day does is increase “variable capital” (again, the money spent on wages) at the expense of “surplus value” (again, the extra revenue which goes to profit for the capitalist, rent on the buildings, intellectual property, etc they depend on, and interest on loans).

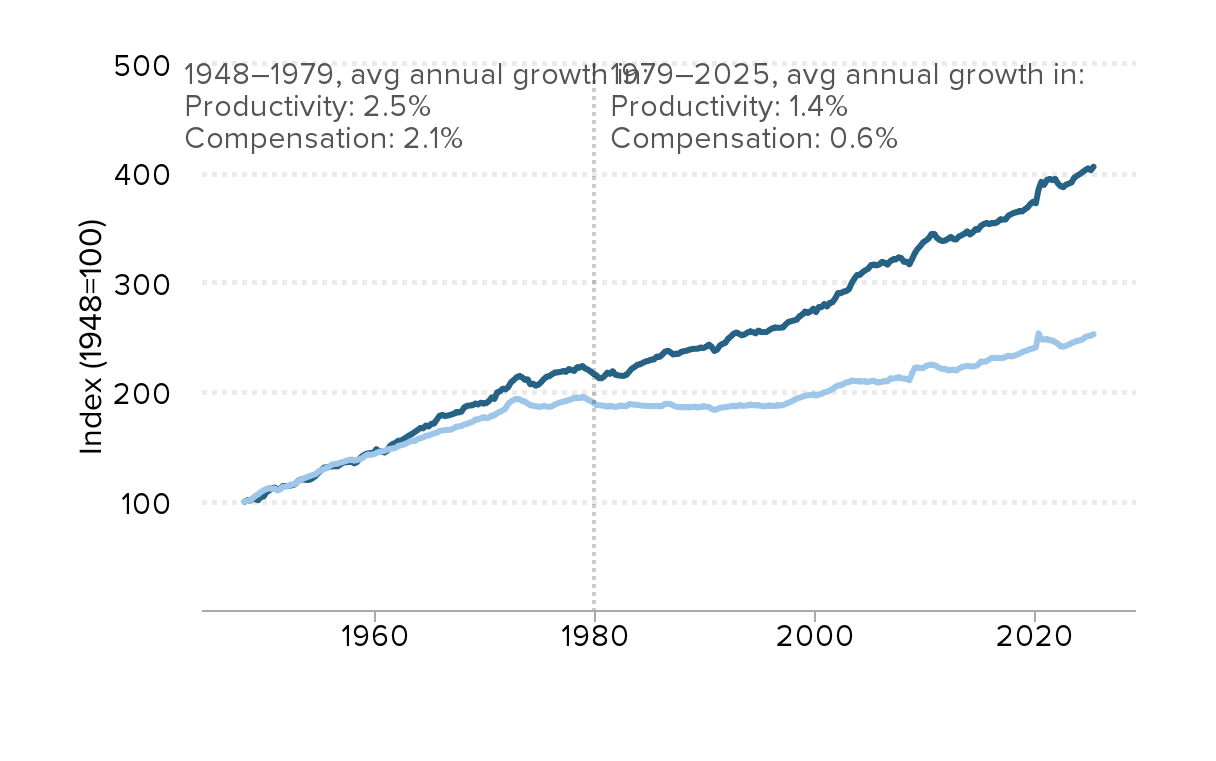

If one is still worried about profit for our wealthy class, let us remember three things. First, productivity gains for the past five decades have largely gone to the wealthy investor class (which is why we’re talking today about who will become the world’s first trillionaire, and not because of hyper-inflation). The benefits of productivity gain have almost entirely gone to capital, not labor, as the following graph shows:

As stated by the Economic Policy Institute, the source of the graph:

The growing wedge between productivity and typical workers’ pay is income going everywhere but the paychecks of the bottom 80% of workers. If it didn’t end up in paychecks of typical workers, where did all the income growth implied by the rising productivity line go? Two places, basically. It went into the salaries of highly paid corporate and professional employees. And it went into higher profits (returns to shareholders and other wealth owners). This concentration of wage income at the top (growing wage inequality) and the shift of income from labor overall and toward capital owners (the loss in labor’s share of income) are two of the key drivers of economic inequality overall since the late 1970s.

Second, the other solution of implementing a UBI would also require the state taxing the surplus. Unless the state is hoping to pay for the UBI by just printing money, which would be radically inflationary without certain radical countermeasures, the UBI will have to be a redistributive policy which taxes the most successful capitalists. If the UBI is to benefit people as much as shortening the working day, it will have to cut into profit just as much with taxes.

Third, not doing anything will anyway cause a capitalist crisis. As already mentioned, without some kind of redistribution of wealth, the capitalist economy will be unable to find customers. Moreover, the working class will become increasingly desperate to latch onto any policy which might solve their problems. Other than a reduction in the working-day, a UBI, or an outright socialist revolution (which I imagine most capitalists would oppose even more than a 30 hour workweek, and which is also unlikely right now), this will be pretty awful stuff like going after immigrants, military keynesianism (which is to say, military overspending and war), racism, sexism, privatizing common lands like national parks, and other unappetizing alternatives. If we rule out any pro-worker changes, right-wing populism in particular with thrive even more than it does now. Not only will these policies cause other harms, they won’t even fix the problem.

In the 19th century, they did shorten the working day, which did lead to a redistribution of wealth downward towards the working class.1 If anything, the success of the 50 hour workweek followed by the success of the 40 hour workweek contributed to the bounty and prosperity the Western working class enjoyed between the late 1930s and 2008. The workers listened to Marx’s advice and fought ceaselessly to reduce the length of the working day, and capitalism didn’t go away when they won. If anything, it flourished just as much as before, refuting the fretting of liberal economists like Nassau Senior. Not only did workers have free time to spend with their family, but there were more jobs to go around and they even had extra money to spend on cars, better housing, appliances, and the other modern comforts of a modest living. This was a far cry from the industrial slums of 19th century England!

Thus, a reduction in the length of the work-day is undeniably a better response to changing economic conditions than a UBI or targeted jobless benefits, and definitely better than doing nothing. That doesn’t make a UBI or jobless benefits bad either, but they should be secondary to this basic demand. It grants more free time to those who do work, and lets their hours of employment get redistributed to those who can’t find work. Yes, it will cut into profits a little bit, but it will prevent most of our society from falling into immiseration with all the political and economic horrors this can produce.

As a caveat, this also means avoiding the kind of harmful reforms we see in France. Today, France is going the opposite direction by extending the retirement age. While France’s retirement age is unusually low, it is worth considering the fact that a lower retirement age has a similar outcome as shortening the working day. Effectively, it is the same thing simply at different time-frames. Where shortening the work-day reduces the amount a person works over a week, lowering the retirement age reduces the amount a person works over the course of their lifetime. By increasing its retirement age, France is merely throwing more workers onto the labor market in an age of automation. Though this may have short term economic benefits for France, it will only hurt it in the long term. Instead of France making its retirement age later in life, the rest of us should be copying the French and demanding earlier retirement.

For those who know your history, you may be aware that May Day comes from the Haymarket Massacre in Colorado when striking workers were fighting for the 40 hour workweek. A grenade thrown at the police by someone led to the police shooting many of the workers, as well as some armed workers shooting back.