How standpoint theory was vulgarized by social justice movements

To identify what went wrong with social movements in the first quarter of the 21st century, we need to go beyond simplistic concepts like "wokeness"

A lot of ink has been spilled in endless debates over the alleged faults of “woke” progressive politics, but there’s very little good content in this debate. The problem with the debate, broadly, is that it remains at the level of vacuous abstractions. Even most progressive, liberal, and socialist people seem to think there is something wrong with the way that they talk about identity, but there is little agreement as to what. There is a sense that it has something to do with the shrill moralism around identity politics, but it goes little beyond that.

One problem that can be identified, at least, involves the way we think about identity. This is what I call vulgar standpoint theory (by this I do not refer to “standpoint theory” as such, but rather a narrow and reductive approach - standpoint theory has its virtues as well as its weaknesses).

Standpoint Theory

Standpoint theory is an epistemological theory which holds that individuals or groups have distinct standpoints within social and political systems. These standpoints determine (in a stronger version of standpoint theory) or influence (in a weaker version of standpoint theory) the different kinds of beliefs which an individual will develop. For instance, a mother has a very different standpoint on the process of pregnancy than a bachelor because she has suffered through it. These differences in belief in turn will go on and inform the political and moral commitments which people hold - a woman, because she has (or at least might yet) experience pregnancy is likely to view the issue of abortion very differently from a man.

Standpoint theory is influenced by the philosophy of Hegel. In his famous “master-slave” dialectic, Hegel argued that the master and the slave have inherently distinct epistemic perspectives. The master sees themselves to be free because they are not forced to work to survive but can make another do so, yet they are alienated from the world of production and dependent on their slave. The slave on the other hand encounters the tangible world through their daily toil, comes to understand it, and develops as a self-conscious subject:

In the master, the bondsman feels self-existence to be something external, an objective fact; in fear self-existence is present within himself; in fashioning the thing, self-existence comes to be felt explicitly as his own proper being, and he attains the consciousness that he himself exists in its own right and on its own account (an und für sich). By the fact that the form is objectified, it does not become something other than the consciousness moulding the thing through work; for just that form is his pure self existence, which therein becomes truly realized. Thus precisely in labour where there seemed to be merely some outsider’s mind and ideas involved, the bondsman becomes aware, through this re-discovery of himself by himself, of having and being a “mind of his own”

Master and slave end up with distinct perspectives on reality, and it is not until the development of a stoic viewpoint which rejects dependence on the outside world that the master and slave can find common theoretical ground - as Hegel says:

The essence of this consciousness is to be free, on the throne as well as in fetters, throughout all the dependence that attaches to its individual existence, and to maintain that stolid lifeless unconcern which persistently withdraws from the movement of existence, from effective activity as well as from passive endurance, into the simple essentiality of thought

Thus, for Hegel, an individual’s knowledge of the world was shaped by their standpoint, but this standpoint was simply a moment in a grand process of intellectual development (if you know your German intellectual history, a kind of bildungsroman for world spirit). Stoicism only gets beyond the standpoint of the slave and the master by granting both a detachment to the conditions that make the slave a slave and the master a master (Hegel famously noted this because Marcus Aurelius and Epictetus, an Emperor and a Slave respectively, advocated strikingly similar stoic philosophies).

Later, Marx and Engels would take up the idea of standpoint to discuss the “standpoint of the workers” and the “standpoint of the bourgeoisie”. In his long chapter from Capital on the working day, Marx recounts how class-conscious workers and capitalists take opposed and distinct views on how long the working day ought to be. The capitalist thinks they should be free to trade any amount of money for any number of hours of work, while the workers demand a universal limit to the working day. Echoing this, Engels argues that different classes take distinct views on morality based on their practices. Later, the Marxist Hungarian György Lukács would formalize this as the “standpoint of the proletariat” in his History and Class Consciousness.

Standpoint thinking did not only develop through the left-wing philosophy of Marx and Engels. Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Morality describes how priests develop morality from the standpoint of the weak as a response to the heroic yet violent morality of the warrior nobility. Nietzsche famously describes how the lambs see the birds of prey that eat them as hateful, while the birds of prey claim they love the lambs - after all, the lambs were delicious. A couple of decades earlier, the Christian existentialist Kierkegaard’s idea of the aesthetic, ethical, and religious individual echoes some themes in standpoint theory as well, although his notions resist clear social and political applications.

Eventually, 20th century feminist, anti-racist, queer, and postcolonial theorists took up the idea of standpoint theory in a new era. They took it up as a way to defend the claims of marginalized groups against the majority. Wealthy white men had dominated science, academia, business, the bureaucracy, and politics in a way that ensured that knowledge production reflected their needs and interests. Marginalized groups needed an alternative epistemology to justify their beliefs. Standpoint theory served this role as they could argue that marginalized groups had a privileged perspective on social problems that was inaccessible to the established “experts”.

As Sandra Harding argued, the standpoint of the oppressed is not a mere perspective but rather an “achievement”. For the standpoint theorist, a woman doesn’t have the “standpoint” of women simply in virtue of being a woman. Rather, the standpoint consisted of a certain amount of social development on the part of the individual:

Only through such struggles can we begin to see beneath the appearances created by an unjust social order to the reality of how this social order is in fact constructed and maintained. This need for struggle emphasizes the fact that a feminist standpoint is not something that anyone can have simply by claiming it. It is an achievement. A standpoint differs in this respect from a perspective, which anyone can have simply by ‘opening one’s eyes’.1

Standpoint theory soon began to filter in to broader social justice circles, and was taken up by activists, social movements, and most importantly, lay people. It became a little bit of philosophy that people could appeal to and drop in an argument. The downside of the popularization of the theory was its vulgarization.

Whenever a theory becomes popularized, it risks becoming vulgarized. When quantum theory becomes popularized, it goes from being a sophisticated way to talk about the interactions and positions of particles to new age woo. When Freudian analysis becomes popularized, it goes from being an interesting and novel theory of the psyche into a way to explain someone’s peculiarities as “daddy” or “mommy issues”. No doubt, Marxists have plenty of familiarity with the ideas of Karl Marx becoming popular vulgarities, and Marxism was (at least to some extent) intended to become a popular theory.

In the case of standpoint theory, its vulgarization led to three changes.

First, it became radically subjective. When Hegel, Marx, Engels, Nietzsche, Fanon, and Beauvoir were discussing the standpoints of various groups, they were always considering both objective and subjective dimensions to their standpoint and the way they interact. Being a worker is not merely a subjective state of affairs. One isn’t a worker because they subjectively feel like one, but because one objectively toils for a wage to survive. Yet for the vulgar standpoint theory, a standpoint is ultimately a matter of one’s subjective viewpoint.

Second, because it is radically subjective this standpoint theory treats epistemic privilege as absolute. Marx never thought a worker was always correct in virtue of being a worker, nor did he think a capitalist was always wrong in virtue of being a capitalist. He saw how Engels, a capitalist, often had far more accurate beliefs about the world than most workers, and he saw that as a man who was generally ruthlessly dismissive of the capitalist class. Yet for the vulgar standpoint theorist, the standpoint of the marginalized person is beyond dispute. It is correct simply in virtue of its own privileged position. There is no longer any need for objective analysis to confirm or elaborate on or develop the standpoint.

Third, because epistemic privilege is absolute, the standpoints in question are increasingly understood as monolithic and static. For Marx, class standpoints are in constant flux as they respond to one another as well as the changing social system they all call home. He argues how workers move from demanding a ten hour working day to an eight hour working day as productivity improves.2 He argues that the abolition of slavery in America will allow white and black workers to unite in a way that is impossible while slavery persists.3 Contrary to this, the vulgar standpoint theory tends to treat the standpoint of black, woman, worker, etc as unchanging social constants shared by most members of a community. Any individual from the group who diverges from this shared, static standpoint must be “self-hating”.

These three positions suffocate the possibility of real discourse, as one does not need to have a discussion if one knows they are absolutely right. It means one can simply claim a position because of who one is, and others are morally obliged to accept this view as the view of the oppressed group. This eliminates the dialectical process whereby we all develop and improve our views through our discourse with good-faith interlocutors. Instead, discourse becomes a kind of moralistic power game.

As Adorno argues at the beginning of his Negative Dialectics:

Dialectics is the consistent sense of nonidentity. It does not begin by taking a standpoint. My thought is driven to it by its own inevitable insufficiency, by my guilt of what I am thinking.

Adorno is arguing that a standpoint as a kind of static identity (identity here not merely being “I am X” but “I am some X, and X has some essential identity that persists through time”). The strength of dialectics is in recognizing the contradictions or moments of non-identity in our existence (and therefore, also, our thinking). No standpoint has a conclusive take on truth, because no standpoint exists without internal contradictions and without incongruencies with our external world. Thus, standpoint thinking is a form of self-delusion that simply paves over the tension inherent in our thought.

Some examples

To show what I am talking about, it might be useful to go from the level of abstraction to real, tangible examples we see in our own current political discourse. To be clear, my description of these four views is in no way indicative of my own views, but merely this approach to standpoint theory applied to different debates. The point is to analyze the argument as a piece of rhetoric, without our own commitments in mind, so we can understand and critique it.

First, on transgender rights we see two predominant discourses - that of the transgender community, and that of the “trans-exclusive” feminist.

A hypothetical transgender activist might argue that transgender people have the privileged standpoint on gender dysphoria and transition. They know they are correct because of their standpoint as a marginalized (transgender woman) person. To question their perspective is illegitimate because they have a privileged epistemic viewpoint. As cisgender women are not transgender, by this view, they cannot speak to transgender issues because they lack the epistemic privilege of gender dysphoria and transition.

A hypothetical “trans-exclusive” feminist might argue that cisgender women have the privileged standpoint on women’s rights. They know they are correct because of their standpoint as a marginalized (“biological” woman) person. To question their perspective is illegitimate because they have a privileged epistemic viewpoint. As transgender women are men, by their view, they cannot speak to women’s issues because they lack the epistemic privilege of womanhood.

Second, on Israel-Palestine, we see two predominant discourses - that of the Palestinians, and that of the Zionists.

A hypothetical Palestinian activist might argue that Palestinian people have the privileged standpoint on the colonization of Palestine. They know they are correct because of their standpoint as a marginalized (Palestinian) person. To question their perspective is illegitimate because they have a privileged epistemic viewpoint. As Zionists are not colonized by Israel, by this view, they cannot speak to the Palestinian struggle because they lack the epistemic privilege of suffering displacement and apartheid.

A hypothetical Israeli Zionist might argue that Israelis have the privileged standpoint on the issue of antisemitism. They know they are correct because of their standpoint as a marginalized (Jewish Israeli) person. To question their perspective is illegitimate because they have a privileged epistemic viewpoint. As Palestinians have not experienced antisemitism, by this view, they cannot speak to what is and is not antisemitism because they lack the epistemic privilege of suffering anti-Jewish discrimination.

No doubt, if you have spent enough time on the internet you will know that these four people are not mere hypotheticals but many really existing people, furiously tweeting, arguing with each other, cancelling their rivals, and getting cancelled themselves. Similar views can be found on a range of other issues.

The problem should be evident. Both sides use the same social justice rhetoric to argue opposed and entirely incompatible views. There is no way for either view to successfully overcome the other, especially because there is no apparent need to justify one’s own view by appealing to objective matters of fact. Nor is there any way to consider the viewpoint of the other side and understand its strengths or contradictions on its own terms. Usually, those who are making these arguments aren’t really concerned with advancing a broader understanding of the questions at play, but merely winning a debate through sheer rhetorical force.

All this has created a toxic discourse where many are no longer committed to a good faith political conversation, but rather building in-groups by sharing (and enforcing) dogma that exists in opposition to some other community with its own dogma. Achieving real change in our cultural norms towards some group is foreclosed, as people would rather simply be right than convince anyone who doesn’t share their current point of view. We do not overcome beliefs we disagree with by learning what they get wrong and confronting them, but instead hope that we will simply wear down the other side with the force of our moralistic assertions.

Why did the vulgarization occur?

I can see at least three sources to this kind of discourse.

First, activist groups usually are more interested with achieving certain immediate political goals. Consequently, they are more interested in taking a rhetorical position that can advance their “cause”. If a moralistic polemic appears as the most expedient means of accomplishing their goal, then that is what will be used. As most Americans are already at least somewhat habituated on certain narratives of oppressed groups “speaking truth to power” to gain their civil rights, this strategy is at least somewhat successful. Serious engagement with the topic is secondary to these pragmatic, polemical ends.

Second, lay people often have an inadequate understanding of these theories as well as their drawbacks. They are, after all, not historians, theorists, philosophers, or scholars but people who may have taken a couple of college courses which they have half-forgotten. This is not really the fault of the lay person, as they have every right to make their grievances heard. Yet all too often we see this discourse being reinforced by politicians, journalists, pundits, and others who probably should know better.

Third, social media privileges short quips and moralistic, aggressive rhetoric to careful and considerate discussion. On top of this, social media is a far more alienating place to have such discussions, as we are interacting with empty avatars instead of real people (there might be real people behind those avatars, but we do not encounter them as real people). These two factors combine to make sure that social media algorithms privilege empty moralism and rhetorical assertion. Though this discourse is not only found on social media, it has definitely made it more widespread and exacerbated its worst tendencies.

I think these three factors have combined with the fact that the vulgar discourse has, to a certain extent, filtered back into the academy. Academics are not immune to the tendencies that vulgarize ideas, even if they are somewhat inoculated. This is not unique to the vulgarization of standpoint theory - the vulgar forms of postmodernism, Marxism, Darwinism, existentialism, quantum theory, and so on all saw their share of academics pushing them. Often, serious academics and scholars vacillate between the serious and the vulgar forms, depending on their context.

That is not to say these reasons are exclusive. I think there are are other cultural causes (I think it fits with a certain kind of narcissism in American culture) as well as material causes (many of which I might connect to the narcissistic culture just mentioned).

Note that this standpoint theory is not unique to one end of the political spectrum. It is found all over, and conservatives resort to a kind of rural white American standpoint theory. You have probably seen the rhetoric before. “Coastal elites just don’t understand real America”, and so on. We’ve also seen how Trump has wholeheartedly embraced a right-wing Zionist standpoint when it comes to the question of academic freedom and the criticism of Israel. This is a view shared by the broad political center in the United States, where moderate politicians have been “canceling” campus protests. Perhaps the most absurd example of conservative standpoint theory was when JD Vance appealed to “lived experience” to ground the claim that Haitian refugees were eating cats and dogs.4 There is still the appeal to the privileged epistemic standpoint, its simply a different standpoint being privileged. Thus, this doesn’t seem to be a mere political problem specific to progressives, but rather a broader problem with our intellectual norms. Its cultural and intellectual roots may differ on the right, but the substance is still the same.

Conclusion

The point isn’t to throw out standpoint theory as such. Certainly, standpoint theory has some truth as a way to defend the claims of marginalized communities, even when it diverges from established narratives. Yet the truth that some people have a privileged perspective on certain problems due to their role in the social system goes way beyond this humble beginning and becomes a totalizing discourse. Rather, standpoint theory must always be situated within a broader historical dialectic that understands how our different views on the world are constantly changing and interacting with one another.

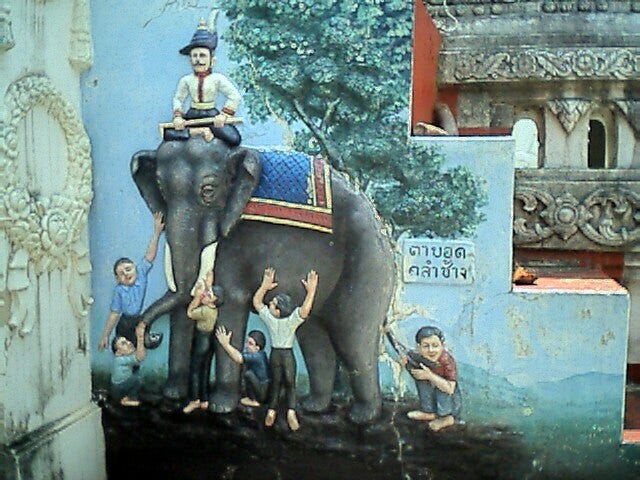

A better way to think about standpoint theory and its role in political debate can be traced back instead to Dharmic philosophy. As a famous proverb shared by Jains, Buddhists, and Hindus describes a group of blind monks who come across an object in the jungle.5 One man grabs a big flappy thing and says it is a leaf. Another grasps a long floppy thing and says it is a vine. One more grabs a longer and thicker floppy thing and says it is a thick rope. A different one grabs a smooth, cool cone and says it is a polished rock. The last man grabs a big, thick cylinder and says it is a tree trunk. Only by coming together in a dialectic can they ever hope to learn that it is an elephant. Thus, we do have different standpoints and these do disclose different dimensions of our shared material reality, but we can only come to the truth by putting these standpoints into a dynamic and good faith conversation with one another.

As quoted on the IEP (https://iep.utm.edu/fem-stan/), from her Whose Science/Whose Knowledge?

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch10.htm

https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1867-c1/ch10.htm

This is a case I talked about in one of my early short essays

Many versions of this tale can be found, even at (of all places) the website of the US Peace Corps https://www.peacecorps.gov/educators-and-students/educators/resources/blind-men-and-elephant/story-blind-men-and-elephant/

This was a very clarifying article. The strong form of standpoint theory is basically group solipsism, you can only understand something by being part of the group. There would be no reason for outsiders to respect your point because theoretically they can't understand you.

The problem with fighting back is that I think the weak version of standpoint theory is true. The conflict then arises because do people view themselves as part of the whole or do they view themselves as distinct groups with competing narratives? Do people believe in the Dharmic proverb or the Rashomon effect?

This is excellent. It really helped me breakdown the concept of standpoint epistemology and how it has been distorted. I find myself both admonishing it and defending it depending on who I’m talking to. Kinda like I’m both woke and anti-woke all at once 🫢. It’s a false dichotomy that gives me a real headache.