Over the past decade or so, there’s been a lot of excitement about BRICS as an alternative to a global economy dominated by the United States, Western Europe, and Japan. BRICS stands for Brazil, Russia, India, China, although it is increasingly incorporating other countries like South Africa and Indonesia. The idea is this - we have a global economic order centered on the dollar and US consumption, but this global economic order marginalizes the global south. With China secured in its place as America’s economic and military peer, however, a new economic order centered around it, India, Russia, and China alongside other major “global south” economies a new order can emerge that turns the global economy upside down.

Surely there is some truth to this, as the economies of the “global south” (or related concepts like the “third world”) are increasingly important as hubs of manufacturing and extraction of important resources, and as they continue to move up the value chain production. Some economists like Richard Wolff defend this notion, arguing that this is a serious challenge to a global economy dominated by Washington DC and its allies. As Wolff presents it, this alliance offers a serious and viable alternative which could soon move away from the dollar as a reserve currency.

Yet there are two main problems with this view. At the very least, these are challenges which the BRICS nations would need to overcome before they could really function as a true alternative.

First, there is a lack of ideological coherence among this bloc of nations. China is ruled by a Marxist-Leninist-Maoist party which claims to be building socialism within its borders (albeit through international trade and a global capitalist economy). Brazil is ruled by a center-left government under Lula, although it’s not clear whether a potential election success by the Brazilian right with “populist” leaders like Bolsonaro would continue this policy. Russia is ruled by a revanchist Putin who has leaned into protecting a powerful kleptocratic class and is actively engaged in a proxy military struggle with NATO powers over Ukraine. India is governed by a rightwing Hindutva (Hindu nationalist) party interested in combining neoliberal economics with suppression against non-Hindus. South Africa is governed by a nominally center-left ANC which has abandoned much of its former economic radicalism, although its changing land policies are suggestive of a turn towards redistributional politics. The other powers joining or thinking of joining BRICS likewise have a variety of economic and political ideologies, from Iranian theocracy to the kind of military-heavy politics we see in Indonesia and Egypt.

This contrasts greatly with the Western economic order, which is primarily liberal capitalist, and the former Marxist-Leninist Soviet bloc that challenged it prior to 1991. The Western economic order shares a common economic universe, once centered on a post-war Bretton-Woods system and now based on neoliberal principles of governance and trade. If anything, the West has become more ideologically coherent, as it began the Cold War as a mix of social democracies and liberal capitalist states (although the return of populism undermines this ideological coherence). The Soviet bloc likewise shared a common Leninist political vision.

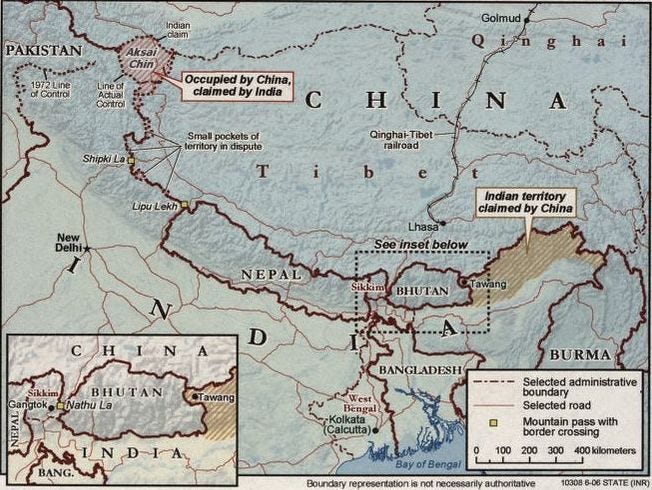

The second problem are the active geopolitical disputes between some of these nations. China in particular has a number of political strategic disputes with the other big dog of BRICS — India. There are active territorial disputes between the two countries along the Himalayas, any one of which could lead to war. These territorial disputes date back to Qing China, and the losses which the gret empire saw over the 19th century. China’s practice of daming rivers in the Tibetan highlands also has caused some disputes between the countries. Finally, many of China’s important allies like Pakistan have active disputes with India (the recent attack in Kashmir against Indian tourists is a tragic reminder of this).

As a rising global superpower, China doesn’t have a huge incentive to surrender these disputes in the immediate term. Likewise, it doesn’t seem like the Hindutva Narendra Modi is looking to resolve all its conflicts with China and Pakistan, and potentially lose face in the process. It is unlikely either country would give up territory they already control. Nor does India have any reason to expel Tibet’s government in exile. Yet for BRICS to function as a viable alternative, China and India will need to sit down and resolve these problems at least for the time being.

We can imagine other similar disputes emerging someday. If Russia suffers some kind of political or economic collapse, what will China do? Will they work to advance the return of Russia’s Marxist-Leninist party? Will they work to save the government? Will they opportunistically align with the liberal forces in Russia? Or will they try to regain territory seized by Russia during the 19th century like Vladivostok? None of these possibilities might seem likely right now, but are all distinct possibilities if Russia loses stability. It might seem odd today, but we cannot forget that China and the Soviet Union ended up going from close allies to a (thankfully brief) shooting war in a matter of years between the 1950s and 1960s.

None of this is to say that BRICS is not an important institution, nor that it cannot provide a viable alternative to the Western economic order someday. Trump’s absurd trade war is a reminder that even China and India (both economically nationalist countries) have some reason to work together against the West. Yet it does mean we need to be nuanced in how we discuss this, and recognize the challenges on international policy for leaders like Xi, Modi, Putin, and Lula in creating a viable alternative to the Western economic order.