The Left Today Talks About the Left Too Much

"Left", "Center", and "Right" are useful concepts, but these have become increasingly uncritical abstractions that conceal as much as they reveal.

Between 1847 and his death in 1883, perhaps the most prolific critic of left-wing politics was Karl Marx. From his publication of The Poverty of Philosophy to the posthumous publication of his “Critique of the Gotha Program”, Marx repeatedly took his fellow socialists and communists to task. Yet unlike the Left of today, he never framed this as a criticism of “the left” or “leftists” - nor for that matter did he criticize “the right”. In fact, he and his comrade Friedrich Engels rarely used those terms. Whenever they did, it was usually to refer to some parliamentary faction or faction within a broader political movement. Instead, he pretty much always critiqued specific ideological tendencies across the political spectrum - anarchists, petty bourgeois socialists, “feudal” socialists, bourgeois socialists, the Chartists, mutualists, monarchists, liberals, Malthusians, Lassalleans, Proudhonists, Bakuninists, and so on.

The terminology of Left and Right goes back at least to the French revolution as the radicals sat on the “left” of the assembly while the conservatives sat on the “right” of the assembly. The left were the egalitarians and republicans, while the right were generally monarchists. Thus, the concept of left and right existed as early as the 1790s, however it was used more sparingly. “The Left”, “The Right”, and “The Center” were not objects of critique or defense as such, but just positionalities in a broader political spectrum.

The left today is rather different. In fact, sometimes it seems like the left today cannot stop talking about the left (and yes, I am aware this short essay is only contributing to this phenomenon, but I must contribute to it to critique it!). There are Progressives who struggle to make the Democrats a “leftwing party” by displacing the “centrists” in favor of Bernie Sanders-style “leftists”. Liberal centrists in the Democratic Party rather worry that “the Left” has too much sway over the Democrats. There are media outlets like Sublation Magazine that focus on “criticizing the Left from the Left”, and political discussion groups like Platypus International that intend to “teach the history of the Left” to itself. Bernie Sanders warns us that “the left has lost the working class”. While some insist the left needs to be more “woke” or is too “woke” (depending on whether they are rightwing or leftwing themselves), others insist the opposite arguing that the left, in fact, is not “woke”.

This is not just an American phenomenon. In Germany, the major socialist party on the political spectrum is Die Linke (The Left) and in France, the leftwing parties rally around La Gauche (also The Left) while in the United Kingdom, the Labour Party has been riddled by conflicts between the left and center across its history, culminating in the rise and fall of Jeremy Corbyn. India has its own “Left Front” constituted primarily by Communist Parties. The list goes on.

When, and why, did this change? As far as I can tell (and I am still researching this question), people began discussing “the left” with more frequency at the time of the German and Russian revolutions - the former was a failure, while the latter was a success (depending on who you ask). The origins can be traced perhapsto the conflict between Reformists (who aimed to realize socialism by reforming capitalism) and their critics in the German Social Democratic Party. Later during the Russian Revolution, the Socialist Revolutionary party split on Left and Right lines, where the Left joined with the Bolsheviks while the Right opposed them. To the left of the Bolsheviks, various anarchists and council communists argued that the Bolsheviks failed to fulfill the promise of the revolution. Against them, Lenin wrote “Left-Wing Communism: an Infantile Disorder” where he levelled many criticisms against the left communists. Later, the Bolshevik Party would face factionalism between the “Left” of the party around Trotsky, the “Right” of the party around Bukharin, and the “Center” of the party around Stalin (though those categorizations were not always fixed, and we all know who won). Likewise, the splits within the German Left led to the conflict between the Communists and Social Democrats in post-war Germany, particularly during the abortive revolution that led to the murder of Communist leaders Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebnecht. Up to Hitler’s consolidation of power, these two parties would battle over leadership of the German Left and the working class.

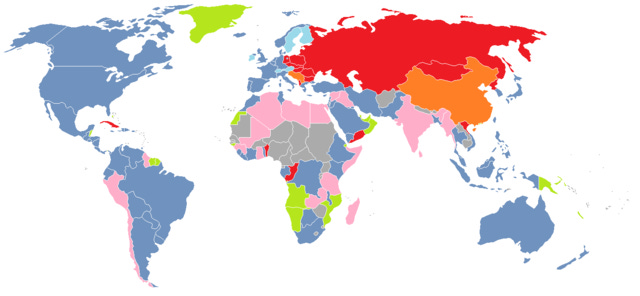

These conflicts were echoed across the globe, as conflicts between moderate social democrats, more radical social democrats and socialists, and various factions of communists struggled for the mantle of leadership on “the Left”. This was reflected on other ends of the political spectrum, like the fascist movement which tried to fuse the political far-right with a handful of leftwing ideas to overcome the moderate right. This discourse would be fully normalized by the time of the Cold War, where Left, Center-Left, Center, Center-Right, and Right (as well as “far Left” and “far Right”) became established concepts in political discourse. In fact, they became global forces where an international left around the Soviet Union and its allies struggled against more moderate political forces (often in alliance with the right) around the United States and its allies.

Why did this terminology emerge? In part, it was to categorize various factions to themselves, for instance so that Lenin could situate the Bolsheviks to the left of the liberals but to the right of the “left communists” and anarchists. It was also to help factions articulate why they knew the path which revolutionary parties ought to take, either by painting other factions as too rightwing or too leftwing. In this respect, it was also suggestive of the kinds of alliances that different factions should build - the “left” of the Republicans, the anarchists, and the Communist Party in Spain, for instance, knew they should work together during the Spanish Revolution and subsequent Civil War. Lastly, it also helped each end of the spectrum to identify what they were not - even if the far left, left, and center left did not agree on what path to take, they all agreed that “the Right” (as in the aristocracy and ultra-wealthy) were dangerous.

There is utility in this language. It is, at heart, an abstraction, and abstractions have their use. My abstract concept of a triangle is useful for me to understand specific triangles, and I can predict what properties they have (for instance, that their angles add up to 180 degrees). I can see the following positive utility of the left/center/right abstraction for those on the political left (as well as those on the right and center):

(1) It allows people to identify themselves as a discrete force in politics and seek common cause with others who largely share their views. Individuals with progressive or radical politics can seek out and identify groups that share their politics.

(2) It allows people across the political spectrum to situate a viewpoint and predict what other people are likely to believe. A person on the left is more likely than not to support gay marriage, oppose imperialistic war, and support sensible workplace regulations.

(3) It allows people to situate their views within wider narratives of historical progress. If I am on “the Left”, I know that I think our society has a long way to go before it is “perfected”, while I know my friends on “the Right” think society ought to revert to some prior state of existence.

(4) It allows political movements in different countries to identify one another around shared principles. Especially by the time of the Second and Third Internationals, socialist parties across the globe organized together as movements that shared common “leftwing” principles. During the Cold War, this would only become more true as communist and socialist parties across the globe banded together despite their massive differences.

Yet today, perhaps it is worth turning a critical eye towards this concept and how it is used discursively and politically. Abstractions can also be vicious when used inappropriately, and can serve to conceal important particularities. The way it has been used frequently leads to the following errors:

(1) it homogenizes the zones of the political spectrum - As we saw, in Marx’s time there was a panoply of leftwing political movements. There were the mutualists of Proudhon, the Lassallean socialists, the Chartists in England, and so on. Yet this is still true to this day. There is still an ideological panoply on the left. There are liberals, mutualists, progressives, anarchists, communists, socialists, and everything in between. Moreover, there are various subfactions of each of these (often overlapping) terms, and conflicts about which of these subfactions represents the best articulation of a particular outlook. Yet when we talk about “the left”, this homogeneity is concealed behind a broader front. In some cases, like Frances La Gauche, this is more evident because it is an alliance of socialists, communists, and other leftwing parties. Yet in the American and British case, the variety of theoretical approaches is concealed.

(2) it justifies overly broad generalizations - as “the Left” homogenizes the left and conceals its internal variety, it fuels broad over-generalizations about the character of the left as a whole. By turning a whole polymorphic category into a single kind, one can make sweeping and overly simplistic judgements about the whole which simply do not accord with reality.

(3) it implicitly removes individuals from the categories they are critiquing - When a leftist critiques “the left”, they are implying that while they are on “the left”, nonetheless the entirety of the rest of “the left” has some fault or failure that only they can see. Thus, despite appearing as a form of self-critique, it is in fact implicitly factional by rejecting the rest of “the left”. Even if the substance of their criticisms have massive kernels of truth, this self-excission is ultimately self-serving. It presents the critic as the one with “the truth” and the entirety of the “left” as in need for this truth.

(4) it facilitates a kind of naive purity politics - frequently, when leftists criticize other leftists, they do so to deny that these other factions are really “leftwing” and thus wrong. It may well be the case that the positions they are criticizing are wrong. For instance, the Greek Communist Party (KKE) opposes gay marriage for various reasons. I do not like this position and think it is misguided, but I do not make the reasons why it is a mistaken position any clearer by saying that this exposes the KKE as a “rightwing” party. The problem with the position isn’t that it shows that the KKE’s leftism is “impure”, rather that their theory on gender politics is hopelessly outdated and confused by overly focusing on the reproductive function of marriage.

(5) it calcifies political dogma - by describing political views as “on the left”, we risk turning it into a mere dogma. It lays out a series of positions that people on “the left” ought to support whether or not we have any kind of theoretical understanding of why we believe these things. For instance, if I describe being “pro-immigrant” as a leftist view, I say nothing about the theoretical reasons why pro-immigrant politics are important. Rather, I am just making a normative claim about what other people on “the Left” ought to believe. I myself am pro-immigrant, but the reason why is not because it is a “leftist” view but for a host of other reasons which I should be able to explain.

(6) It makes politics narcissistic - this is perhaps the most dangerous flaw of the terminology alongside (1). The more the left discusses itself, the less it centers the social classes it intended to represent. Historically, the left was clearly united in advancing the interests of the working class first and foremost, and this was its defining feature (though importantly, not one present in the original French left in the 1790s). Over time, this would be extended to women and minorities (for instance, when Marx unabashedly supported the Union cause during the Civil War so as to abolish slavery). The more the left talks to itself about what it is and what it ought to believe, the less it is talking about and to workers, colonized peoples, peasants, paupers, immigrants, the unemployed, etc. The workers are no longer the object of political action, but “the Left” as a political faction. Thus, large swaths of the left risk becoming (and often functionally are) just circles of political activists talking to themselves about what they ought to believe and ought to do without thinking of those they ought to be organizing.

None of this is to say that the language of “right”, “left” and “center” ought to be abandoned. It does have some utility, and there are real historical reasons why it came into being. We still live in the world created by the conflict between Bolshevism, Social Democracy, Liberalism, and Fascism, and from the United States to China, these ideologies remain dominant in one form or another. So long as these terms help us to understand and explain this world, there is use for them.

Nor is this a phenomenon unique to the left. It is also present on the right and the center, as religious conservatives, paleoconservatives, neoconservatives, capitalist libertarians, theocrats, nationalists, and fascists define themselves as “the right” and the political establishment define themselves as “the center” standing against both political “extremes”. Inasmuch as these terms have certain advantages and drawbacks for leftists, they also do for the right. Language like “the Right” homogenizes these very different groups, justifies overy broad generalizations, and so on. The same can be said for language on “the Center”.

We need to be wary of how these terms have become reifications. We have created this abstraction for historically specific reasons (both theoretical and practical), but the category appears to us today as simply a brute fact. We forget the historical origins of these terms - even if we are aware of their genesis in the French Revolution, we forget why they became popular. In so doing, we forget the nature and limitations of these categories. Of course, if there is one critical lesson Marx left for “the Left”, it is to ruthlessly critique reifications so we are not unwittingly subject to their theoretical and practical risks. There is a good reason why Karl Marx, the most insightful thinker in the history of the Left, did not treat the Left as an object of critique or support in itself.

Instead of abandoning this language outright, we ought to be more sparing in how we use it, when, and for what purposes. We also ought to be more self-aware of the limitations of this language, and how it can conceal or mislead as much as it reveals. And we ought at least to talk about “the Left” as a homogenous whole less and speak more about the various factions, tendencies, and theories that constitute it.

I'm so glad that Varn Vlog covered your article! It does seem, to me anyway, that people would do better to debate and focus on issues more separately and specifically rather than trying to pigeonhole nuanced ideas--and aren't they all--into easy and oversimplified black-and-white (left-or-right) schemes. I hope you and yours are doing well! 🧡