The forgotten importance of economies of scale

How a boring economic concept grounds the basis of China's success, and the challenges facing America

From the conservative economic vision of America’s ascendant “populist right” to the repurposed neoliberalism of the “abundance” discourse, there is an increasing realization among the American ruling class that the US economy is finally beginning to fall behind that of China. Something must be done to get around this problem and maintain economic dominance for the United States. What this “something” is differs — it might be tariffs, it might be zoning reform, or it might be building new cheap coal plants. What all this discourse forgets is the importance of economies of scale.

Simply put, economies of scale refers to the increased efficiency that comes with producing, moving, and distributing goods at ever-larger scales. We’re all familiar with it in the savings we get from buying a gallon of milk over the smaller cartons, or buying other goods in bulk. We all see the effects of it when we drive through the “main street” of some small town where all the stores have been clearly abandoned for decades, but the Walmart and Target five miles away are doing great. Yet the importance of economies of scale gets forgotten in political discourse.

Economies of scale were of critical importance for early liberal economists like Adam Smith as well as the critics of liberal economics like Karl Marx. Adam Smith saw how businesses could outcompete their rivals with larger and more efficient systems of production. For Adam Smith, the larger businesses could achieve more production by hiring more people and thereby enabling a more elaborate division of labor. One man making needles has to do all the tasks required to make a needle, but one hundred men can produce far more needles per person as each individual takes on a single specialized role in the process.

Marx built upon this by pointing out how economies of scale enabled capitalism to emerge in the first place. As Marx argued, there was a certain point at which capital was accumulated where it could begin buying up more efficient machinery and using that machinery more effectively. At this point, businesses could produce more of a good with the same amount of labor, thereby allowing them to beat out their rivals.

As Marx argued, these economies of scale compounded in a kind of exponential growth, as ever-larger industries benefitted from ever-greater economies of scale. This came with capital replacing more workers with automation. So long as labor costs were not dirt cheap, it is generally more efficient for capitalist firms to invest in more machinery and automation to reduce labor costs. Machinery (alongside land, buildings, raw materials, and so on) was a part of what Marx called “constant capital”, as opposed to the labor provided by workers which was “variable capital”. Without getting into the woods of Marx’s distinction between these two concepts, how they relate to profit, and so on, the important takeaway is that the more constant capital a business accumulates the more efficient their use of labor becomes. Growth, therefore, leads to an ever-more efficient use of the existing pool of workers, as businesses plow more of their profits into constant capital so that they can more efficiently exploit their workforce.

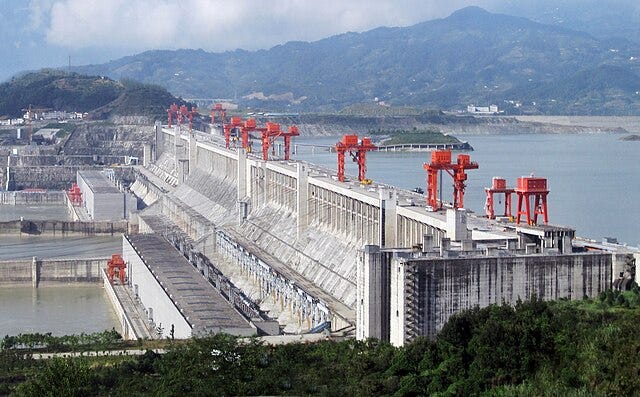

As an example, I was at the Hoover Dam earlier, marveling at this great piece of engineering and the art-deco architecture that clearly dates its creation. What is really remarkable about it is how much power it produces and how much water it provides for the American south-west. It can only accomplish this because of the massive scale of the project. Yes, it required more construction workers to create a public work so massive, and we need more people to monitor and maintain it. Yet the added cost gets us far more energy and water per dollar invested than had they built a smaller dam.

Why are these economies of scale so important? For one thing, because it is the goal of economic growth as every firm is aiming to achieve economies of scale over their rivals. Every large company wants to be the Walmart that puts the small “mom and pop” shop out of business, not the small “mom and pop” shop. For another thing, because it is what enables further growth, as the only firms which are best positioned to continue growing are those which have achieved economies of scale. Finally, it sets the limits of growth, as there is always some scale a business or country can achieve before further growth becomes inefficient. Plenty of firms have gone under by expanding too fast to really benefit from the economies of scale they would need for that growth to pan out.

What does all this have to do with China and America? Simply put, China will always have an advantage in the game of economies of scale. First, China simply has more people, and these people are largely collected along the coastal areas or along major rivers. This enables its firms to enjoy far grander economies of scale than other countries, except perhaps India or a few smaller but densely populated states like Japan and Vietnam. Second, the Chinese government understood economies of scale and accounted for them in their planning. China has invested vast sums into its infrastructure, and infrastructure benefits from economies of scale too. If you build a train line between two cities, you can have one hundred people or one hundred thousand people use that same train line every day. You will need more train cars and bigger stations, but you won’t need more tracks. You can use fewer engines per person with the hundred thousand passengers. You will have more empty seats in your trains with the one hundred passengers.

All this has enabled China’s rapid growth. It seems like the Chinese government may have forgotten much of Marx’s writings on economics, but that part on economies of scale stuck. It has built massive ports that can send goods across the globe, freight lines to bring goods to these ports, and massive hydro power dams that dwarf even America’s Hoover Dam. It has built massive passenger rail systems to move workers to and from their jobs. This investment is more efficient because China has more people, and this investment in turn allows China’s people to produce more efficiently. Thus, there is a kind of happy cycle of production which China benefits from. It is why Trump needed to slap tariffs of over 100% to effectively block Chinese trade - they’re simply so much more efficient than the competition.

How can the United States compete with this? They have a little over 1/5th of China’s population. The only way for America to reliably catch up on that front is the very mass immigration which Republicans reject in principle, and that Democrats reject out of political pragmatism (just see Biden and Harris turning into anti-immigration hawks in a failed effort to beat Trump). Even if China’s declining birthrates continue to drop and if Vance’s pro-natalist project exceeds his wildest dreams (the second is … unlikely), it would take generations for America’s population to outstrip China’s (and there’s nothing to prevent China from avoiding the fate of Japan by bringing in immigrants). Just as importantly, the United States has totally failed to adequately invest in infrastructure since Eisenhower built the highway system. Obama’s stimulus spending and Biden’s “Build Back Better” and “Inflation Reduction Act” alike failed to reach the kinds of spending America needs to get ahead. What’s worse, America tends to be wildly inefficient in how it spends. America’s economy, in many ways, seems like an intentional effort to reject the economies of scale - yes, we have our Walmarts beating “mom and pop” grocers into oblivion, but Americans prefer their gas guzzling pickup trucks to trains and massive, land-greedy “McMansions” to high density housing.

All this is to say, Americans do not seem to understand the material forces behind China’s rise. America is a country run by lawyers, while China is an economy largely run by engineers. They might be ruthless autocrats, but they know how to achieve economies of scale through massive state-backed investment and organized long-term growth strategies. The best America seems to offer in response is a fictitious AI boom whose only benefit will be to render many Americans jobless while pumping out crap content and consuming vast amounts of energy and water.

Why don’t American politicians and pundits discuss economies of scale? Perhaps it’s because to do so would admit the fundamental problem that America has hit the logical limits of its growth. It cannot achieve greater economies of scale without disrupting the American way of life. Or perhaps it’s because the solutions to this problem have already been ruled out by political and popular orthodoxy. Or perhaps it’s because economies of scale are fundamentally alienating and disempowering, as it means that the only way to compete with rivals is to submit to ever-larger, ever-more centralized, and ever-less democratic economic institutions that dominate our lives. But we do need to reckon with this reality eventually, even if we don’t like what it tells us.