No, "tech trees" aren't real

How an analogy to computer games deceives people about the nature of technological progress

In the sciences, models are useful things. Very useful, in fact. Generally, they serve at least three functions - to make a more simplistic basis for predictions, to provide a direct analogy, and to provide an indirect analogy. The broad point is that many phenomena are too complex to be understood directly and a less direct approach is necessary. By using the model as an analogy, we can draw a general mental picture of how some structure or system works.

We can see the three uses of the model in the example of the Copernican model of the solar system. Initially, Copernicus put forward his model of the solar system as a way to better predict weird phenomena that the geocentric Ptolemaic model failed to do - specifically, things like retrograde motion. Yet Copernicus was careful about challenging the geocentric model too directly, and didn’t have the evidence to put forward heliocentrism as a description of how the cosmos worked. Later, Galileo and Kepler found adequate evidence for the heliocentric model as a picture of the cosmos, as well as adequate modifications (like Keplers addition of elliptical orbits instead of circular ones). Thus, heliocentrism went from being an interesting model that could make useful predictions to an actual rough description of the cosmos. Later, Niels Bohr would use this model as a way to imagine the structure of the atom. Thus, we can see how the heliocentric model has found all three uses over its long history.

Other models populate science and popular common sense understandings of the universe alike. Once, we used the mind as a model to understand computers, and increasingly we are using computers as a model to understand the mind.

Models certainly have their advantages, but they have their disadvantages too. Models can conceal as much as they reveal. Often, they serve to over-simply complex phenomena in vicious ways. The intuitive truth of the model is deceptive, as it feels true simply in virtue of “making sense”.

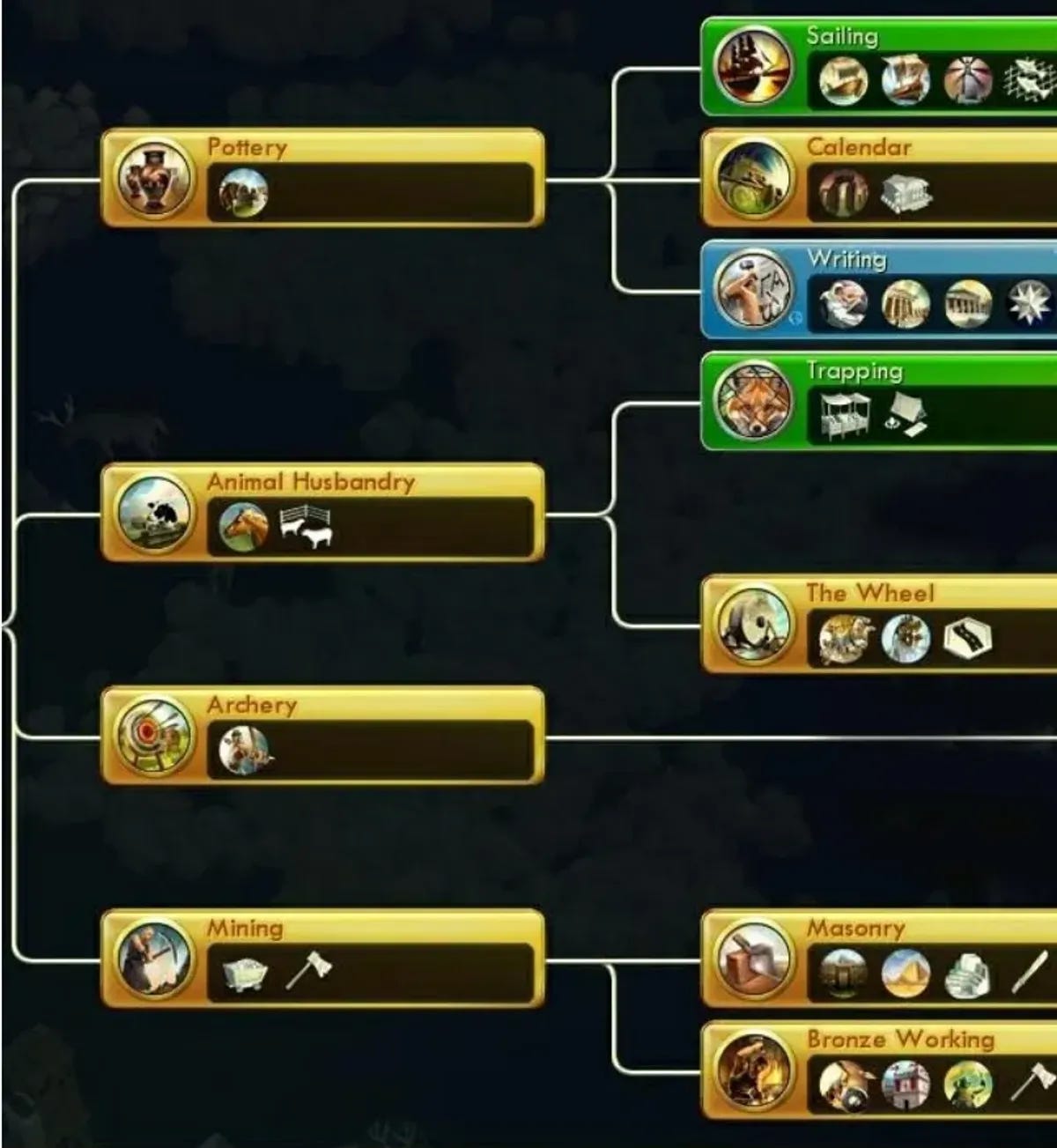

One particularly dubious example is that of the “tech tree”. Technology trees are a basic feature of many (most?) strategy games on the computer, and involve researching prerequisite technologies to unlock research on future technologies. We might research agriculture so we can research animal husbandry in a game like Civilization, coal engines to research trains in a game like Victoria 3, or in a game like Starcraft we have to build a factory before we can make tanks.

As a feature in computer games, tech trees can be fun and useful. They require players to plan out a strategy well in advance, and they capture the fact that the development of one technology often comes as a consequence of some prerequisite being met. The developers of Victoria 3 are not wrong to make trains derivative of the steam engine. Thus, tech trees simultaneously achieve the two (often opposed) goals in game design: playability and immersion (often, what makes a game more fun makes it less immersive, and what makes a game more immersive, makes it less fun).

Yet the idea of the “tech tree” isn’t really an accurate description of the history of technological development. It levels out and oversimplifies the way technological change works, and presents a universal trajectory of development from “less” to “more” advanced. What’s worse, while it’s not quite linear, the tech tree functionally comes close.

In reality, the way technology advances is far more diverse and complex than the tech tree captures. Societies can achieve all sorts of incredible advances in certain areas while lacking ideas and technologies that are ubiquitous elsewhere.

The civilizations of the New World prior to the “discovery” of Columbus serves as an excellent example. New World civilizations lacked certain developments taken to be basic and foundational to civilization. They lacked metalworking beyond soft metals like copper, gold, and silver, and they only used wheels for children’s toys and calendars. They primarily continued to use stone for tools, and they lacked various architectural features like the arch which had allowed European and Middle Eastern civilizations to build large open spaces. Thus, they are deemed technologically backwards civilizations whose defeat was inevitable. The contribution of technology was one-way, as the New World was catapulted into the Renaissance by the Conquistadors who tore down the pyramids to build giant cathedrals.

Yet this is a stark oversimplification. Yes, these civilizations lacked certain technologies taken to be “basic” by Europeans, thus by the standard of a Eurocentric tech tree they were “backwards”. This view overlooks the fact that New World civilizations had developed a whole variety of other technologies that made their lives better in various ways.

Take the Nahua civilization in Mexico (the basis of the Aztec Empire). This civilization had developed methods of agriculture that were vastly more productive than anything in Europe. The chinampa farms in the Valley of Mexico were floating gardens built into the lake floor, and were fertilized with sediment from the lakebed. These fields were incredibly fertile, to the point where farmers could get many harvests of corn from the same plot in a single year. This was assisted by a network of aqueducts which channeled freshwater to the lake and levies which kept the saltwater out (the Aztec philosopher-king Nezahualcóyotl is credited with building this system up). Chinampas can still be found today in Mexico City in Xochimilco, where farmers still grow maize and vegetables.

Thanks to their agricultural prowess, today we have maize, tomatoes, many types of chili, chocolate and vanilla (which were harvested primarily by Mayans, not the Aztecs, but was consumed by the Aztecs), cochineal dye (a small bug that lives on the nopal cactus), and many others (in fact, our words for Tomato and Chocolate can be traced back to Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs).

Moreover, the Aztecs practiced a form of polyculture agriculture that allowed them to maximize the productivity of the land as well as the nutritional content of what it produced. This involved growing maize, squash, and beans together. As the ecological costs of monoculture agriculture have come under increasing critique, there has been renewed interest in this Nahua farming technique (we still have things to learn from them, apparently).

This allowed the Aztecs to develop a network of massive urban centers, most notably Tenochtitlan and its sister city Tlatelolco which, combined, had a population of 200-300,000 people. Yet the Valley of Mexico (where Mexico City is today) had numerous other large cities like Iztapalapa, Xochimilco, and Coyoacan (which have since become municipalities within Mexico City).

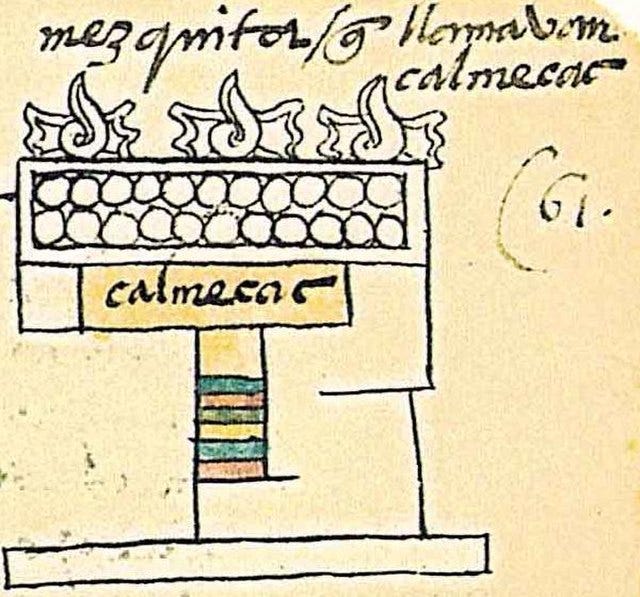

Moreover, the Aztecs developed a form of compulsory education for their citizens, arguably the first to implement such a system. The nobles went to the Calmecac where they learned theology, astronomy, mythology, agronomics, and the Aztec writing system among other things, while commoners went to more simple schools that emphasized practical skills. This was at a time where in most civilizations, schooling was reserved for a tiny elite intended to engage in government, trade, and religion.

New World civilizations had developed other ideas like the number zero which was still controversial in parts of the Old World still bound by Aristotle’s dictum that nature abhors a vacuum (this idea would eventually be adopted for the simple fact that it made bookkeeping easier).

This isn’t to say the Aztec Empire was more advanced than the Spanish who defeated them, but it is to say they weren’t really less advanced either. Rather, they had advanced in a very different direction. Eurasian civilizations had taken a very different trajectory where technologies like gunpowder, chariots, large ships, and metal had proliferated between competing states. The Aztecs had no problem using obsidian weapons since their rivals also used obsidian. Obsidian was more than adequate for their purposes - its often sharper than metal weapons, its main disadvantage being that it’s not very resilient and chips easily (it is worth noting that most of the soldiers under Cortés’s command were actually Nahua Tlaxcalla warriors also using obsidian weapons). If anything, the biggest technological failure of the Aztecs was their lack of a resilient state system, since most of their empire was made up of tributary states who didn’t identify with the Empire at all (many of whom simply sided with the Spanish).

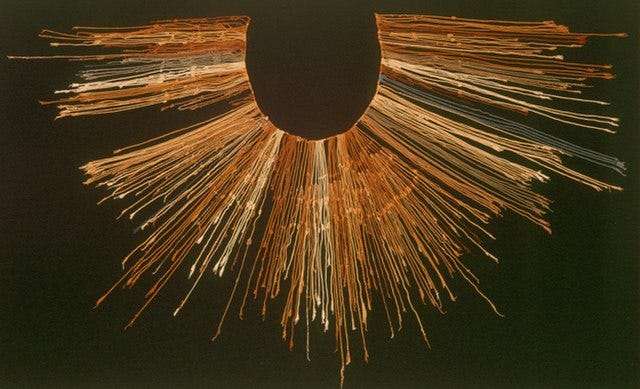

The Inca likewise developed a series of distinctive technologies not seen in Eurasia. While the Aztecs, Zapotecs, and Mayas did develop writing, the Inca did not. Yet they did develop an interesting form of bookkeeping called the quipu that used chords of string to record data and other important information. This did not have the flexibility of a writing system, but met the bureaucratic needs of the Inca state perfectly as they were able to record precise information about production over an empire of as many as 10 million people. The quipu granted their bureaucracy the capacity to plan economic activity across their empire in a form of early planned economy.

Their brilliant masonry allowed them to build colossal buildings that are far more resilient to the earthquakes that rattle the Andes than European architecture. Of particular interest is how they were able to build massive blocks that fit so tightly together that they did not even need mortar.

Their system of terraces allowed them to grow food in places no European would ever farm. Their own agricultural discovery, the potato, would end up spreading across the globe just as much as the tomato (no, the potato did not come from Russia or Ireland, just as the tomato did not come from Italy!) Many of these terraces are still in use to this day thanks to the resilient engineering the Incas had developed.

Lastly, the Inca built a masterful network of roads running across their Empire. These roads featured sophisticated rope bridges (a technology not found in Europe at the time) which were relatively easy to build, safe, and reliable (contrary to the trope of the sketchy collapsing rope bridge)

There are other examples from elsewhere. Polynesians built boats that could cross the expanse of the Pacific Ocean, the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) developed a model of government that Rousseau drew inspiration from, and the Inuit developed all sorts of techniques to survive in their hostile arctic environment.

All of this is to say, the traditional way of thinking about technology and advancement that is embodied in the model of the tech tree utterly fails to capture the reality of technological change. Technology does not develop along a linear path as a civilization moves from “basic” to “advanced”. Rather, civilizations develop specific technologies to meet the specific challenges found in their own environment. They adopt technologies from their neighbors, leading to proliferation of technology along the logic of geographic constraints.

The model of the tech tree misses this complexity, and reduces technological change to state research projects along a universal pattern of progress. It misses the way technology develops organically within a society that is rooted in a particular climate, ecosystem, and geopolitics, often without intentional decisions by the state. When technological development is done with intention, often this occurs through stealing or trading ideas from other civilizations.

Inevitably, the “tech tree” assumes that the technology of the historical victors were more advanced than the colonized civilizations of the New World. Gunpowder is an “advanced” technology in the Civilization games, but not the Inca terrace and Aztec chinampa. Yet was gunpowder that much more sophisticated? To say it is assumes that technology is best evaluated in terms of conquest and competition. It assumes a somewhat linear notion of development.

The tech tree itself is built upon the classic model of “stone age”, “bronze age”, and “iron age” civilizations marking the use of stone, bronze, and iron tools respectively. This was the pattern followed by most Eurasian and African civilizations, and is somewhat accurate when talking about China, Sumeria, and Rome. Yet we’ve already seen how “stone age” civilizations in Mexico and Peru had all sorts of advances unfamiliar to the civilizations of the Old World. Yes, they were ultimately defeated by the European conquerors (although some Inca held out until the late 1500s, and some Maya held out until 1697), but their discoveries enriched the old world as much as the discoveries of the Old World enriched the new world (although animal husbandry, one of the advances of the Old World, fueled the terrible pandemics that beset the New)

We know models are often useful, especially for the systems of the cosmos. Yet when it comes to society, anthropology, and human history, models tend to conceal and perpetuate dubious assumptions. We should be critical in applying them in such fields, and question whether we are being misled by our assumptions.

Civ 5 is great, and the Vox Populi mod is outstanding - a whole new game.