How Marx's thinking made capitalism a little less awful

We have decent lives today because of the working class movement to shorten the working day - a movement which Marx gave theoretical rigor

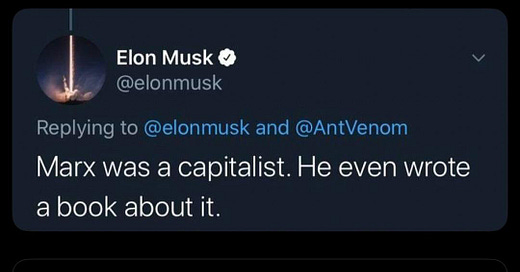

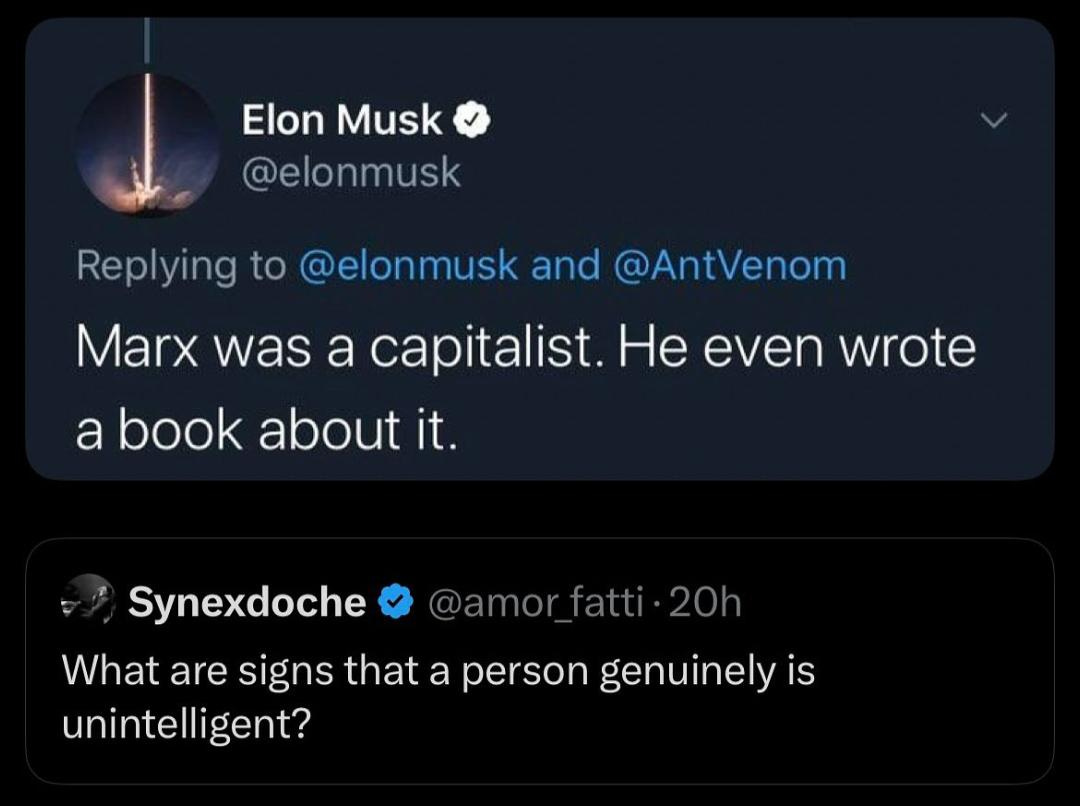

It is often argued that the authoritarianism and eventual collapse of the Soviet project refuted the economic and political thinking of Karl Marx. Yet what this argument misses is the way Karl Marx’s ideas influenced the trajectory of modern capitalism too, and for the better. I am sure I do not need to explain to you that Marx was an avowed communist (though evidently, Elon Musk needs that lesson). Yet his arguments shaped the trajectory of the wider worker’s movement, and helped set its agenda.

Karl Marx did not intend to reform capitalism, and did not think capitalism could be reformed in a way that would end the exploitation of labor, alienation, and ecological devastation. Yet he did strongly advocate for specific reforms within capitalism that would simultaneously make the lives of workers, improve the political consciousness of the working class, and accelerate the emergence of socialism. Many of the reforms advocated in the American New Deal and by European social democracy can be traced back to ideas that Marx supported. Of particular importance is the limit on the length of the working day.

Shortening the working day

The most obvious and compelling example is Marx’s strong advocacy for a shortening of the working day. In Marx’s time, it was normal for the industrial working class of England to be subjected to absurdly long work weeks. Workers were working up to 7 days a week, and for work days that could extend to the full 24 hours. The avowedly secular Marx even went so far as to defend the Sabbath, pointing out that workers didn’t even enjoy their free Sundays. The only limit was the point at which workers were physiologically no longer able to keep themselves awake. You could surely imagine the dangers of working a 14 hour shift in a steel smelter next to massive cauldrons filled with iron lava, or on lathes that could sever a misplaced limb with ease.

In the last week of June, 1863, all the London daily papers published a paragraph with the “sensational” heading, “Death from simple over-work.” It dealt with the death of the milliner, Mary Anne Walkley, 20 years of age, employed in a highly-respectable dressmaking establishment, exploited by a lady with the pleasant name of Elise. The old, often-told story, was once more recounted. This girl worked, on an average, 16½ hours, during the season often 30 hours, without a break, whilst her failing labour-power was revived by occasional supplies of sherry, port, or coffee. It was just now the height of the season. It was necessary to conjure up in the twinkling of an eye the gorgeous dresses for the noble ladies bidden to the ball in honour of the newly-imported Princess of Wales. Mary Anne Walkley had worked without intermission for 26½ hours, with 60 other girls, 30 in one room, that only afforded 1/3 of the cubic feet of air required for them. At night, they slept in pairs in one of the stifling holes into which the bedroom was divided by partitions of board. And this was one of the best millinery establishments in London. Mary Anne Walkley fell ill on the Friday, died on Sunday, without, to the astonishment of Madame Elise, having previously completed the work in hand. The doctor, Mr. Keys, called too late to the death-bed, duly bore witness before the coroner’s jury that

“Mary Anne Walkley had died from long hours of work in an over-crowded work-room, and a too small and badly ventilated bedroom.”

In order to give the doctor a lesson in good manners, the coroner’s jury thereupon brought in a verdict that

“the deceased had died of apoplexy, but there was reason to fear that her death had been accelerated by over-work in an over-crowded workroom, &c.”

Naturally, a human being working longer than a full day in a crowded room with poor ventilation, consuming nothing but coffee, wine, and booze, is not good for health.

This issue animated Marx, and his chapter on the working day is longer than any other chapter of his Capital (the book Elon Musk evidently thinks was a book explaining how capitalism was good, actually). He systematizes the issue of the length of the working day and endeavors to explain why the working day gets even longer, instead of shorter, as industry becomes more productive.

The intuitive thought most people had prior to the industrial era was that more efficient means of production would shorten the working day. If we can produce something more efficiently, it should reduce the amount of time we need to spend making it. Yet Marx realized the rather obvious truth that this machinery was expensive and also was likely to become obsolete as soon as even more productive technology gets invented. To extract maximal value out of the machine before it has to be replaced, industrialists must keep it running at all times (in some cases, like smelting, this is even more the case as the blast furnaces that melt the metal cannot be turned off without requiring them to be heated up again at high cost (moreover, any iron within the blast furnace will solidify, potentially ruining it). In fact, the issue of blast furnaces is so acute that recently the British government reversed their longstanding neoliberal policy of rejecting state ownership by nationalizing their only remaining steel mill when rumors came out that its Chinese owner was thinking of turning them off.

In the 19th century, there was an intense and committed worker’s movement to shorten the working day to 10 hours a week, eventually moving to 8 hours a week. More strict requirements were pushed for children and women whose working days were almost as unregulated as that as men workers (in an age of formal gender equality, the issue of women working as many hours as men may seem alien as a “problem”, but the problem with children working 70 hours a week should be obvious).

Karl Marx defended this movement, explaining that it was ultimately the most important effort for workers to engage in. In his 3rd volume of Capital, he calls shortening the working day was the “basic prerequisite” for creating a free, rational society without alienation and exploitation.

The actual wealth of society, and the possibility of constantly expanding its reproduction process, therefore, do not depend upon the duration of surplus-labour, but upon its productivity and the more or less copious conditions of production under which it is performed. In fact, the realm of freedom actually begins only where labour which is determined by necessity and mundane considerations ceases; thus in the very nature of things it lies beyond the sphere of actual material production. Just as the savage must wrestle with Nature to satisfy his wants, to maintain and reproduce life, so must civilised man, and he must do so in all social formations and under all possible modes of production. With his development this realm of physical necessity expands as a result of his wants; but, at the same time, the forces of production which satisfy these wants also increase. Freedom in this field can only consist in socialised man, the associated producers, rationally regulating their interchange with Nature, bringing it under their common control, instead of being ruled by it as by the blind forces of Nature; and achieving this with the least expenditure of energy and under conditions most favourable to, and worthy of, their human nature. But it nonetheless still remains a realm of necessity. Beyond it begins that development of human energy which is an end in itself, the true realm of freedom, which, however, can blossom forth only with this realm of necessity as its basis. The shortening of the working-day is its basic prerequisite.

In his first volume, he defends the shortening of the working day in the strongest terms possible:

It must be acknowledged that our labourer comes out of the process of production other than he entered. In the market he stood as owner of the commodity “labour-power” face to face with other owners of commodities, dealer against dealer. The contract by which he sold to the capitalist his labour-power proved, so to say, in black and white that he disposed of himself freely. The bargain concluded, it is discovered that he was no “free agent,” that the time for which he is free to sell his labour-power is the time for which he is forced to sell it, that in fact the vampire will not lose its hold on him “so long as there is a muscle, a nerve, a drop of blood to be exploited.” For “protection” against “the serpent of their agonies,” the labourers must put their heads together, and, as a class, compel the passing of a law, an all-powerful social barrier that shall prevent the very workers from selling, by voluntary contract with capital, themselves and their families into slavery and death. In place of the pompous catalogue of the “inalienable rights of man” comes the modest Magna Charta of a legally limited working-day, which shall make clear “when the time which the worker sells is ended, and when his own begins.” Quantum mutatus ab illo! [What a great change from that time! – Virgil]

Equating the shortening of the working day favorably to the Magna Carta was a provocative line, especially when talking about English workers. The Magna Carta, of course, was the original foundation of the eventual development of modern liberalism and rights (albeit in its earliest form) as the document which delineated the rights, privileges, and obligations of English subjects before the King. It set the seeds that would grow into the modern Anglo-American liberalism expressed by Locke, Paine, Washington, Jefferson, and Lincoln. Yet Marx is saying the benefits of shortening the working day is more materially fundamental to universal betterment than that!

As Marx explains elsewhere in the text, shortening the working day kills two birds with one stone - not only does it protect workers from over-work, but as businesses will still want to keep their factories operating when workers are off their shifts, they will need to hire more workers. Thus, shortening the working day is the tool which will unite workers with the unemployed in a shared cause. Also, the issue cannot be solved in a single factory, as any factory that becomes less profitable by shortening the working day will be crushed by its competitors. Thus, shortening the working day also becomes a national cause as workers unite to make the limited working day a national level law.

Marx would go on to advocate this position as the most fundamental development in the First International (the International Workingmen’s Association) which he helped found and guide. This body in turn informed worker’s movements across Europe and in the United States and helped guide its principles.

In Marx’s own time, the worker’s movement in England achieved a 10-hour working day (with some carve-outs and loopholes). After his death, the movement would continue across national borders. Notably, May 1st is international worker’s day in memory of the Haymarket Massacre in America, where workers striking for the 8 hour work day were killed by the police (more would later be executed on allegations of violence towards the police).

The 8-hour workday eventually became the norm across the Western world. It has become the law in the United States, and has been for decades. Employees can work for longer than 40 hours a week, but will get overtime as compensation (and a nice incentive for employers to find more employees instead of just overworking existing employees). It is a reform that, perhaps more than any other, has made modern capitalism liveable as workers have the time to enjoy with their family, organize, watch movies, play games, go on vacation, and sleep properly.

Yet it’s a reform we increasingly take for granted. Moreover, it’s one that is increasingly at risk of being reformed away by governments looking to “increase economic freedom” at expense of the working class. It’s also a cause we’ve largely forgotten. Once upon a time, famed capitalist economist Keynes speculated that, by our own time, we would enjoy a 17-hour workweek based on projections of improving productivity. Yet beyond the platforms of a few more radical social democrats like Bernie Sanders and Jeremy Corbyn, there isn’t much of a push to shorten the working day more. Instead, we’ve seen a re-emergence of the old, capitalist arguments Marx so effectively debunked that shortening the working day would be apocalyptic for capitalism by negatinv the profit margin. Even if a Corbyn or a Sanders took power and endeavored to shorten the working day, they are unlikely to succeed without a large movement of workers behind them.

Conclusion

Thus, Marx did not only influence the trajectory of the Soviet Union and China, but also the very capitalist world be opposed and criticized. He influenced it through the worker’s movement he helped organize, defend, and advocated for. They fought to realize Marx’s idea on the working day, convinced of the justice of this cause by their own conditions and confident that it was not economically devastating thanks to the economic arguments advanced by Marx. When someone tells you Marx’s ideas don’t work and prattle off some vacuous argument about the collapse of the Soviet Union or China’s market reforms, reflect on the value of the 8-hour working day and the fact that this simple reform is what ensures we have at least a little bit of time to spend with our friends and family.

It wasn’t only the working day. It was the limits on child labor, the extension of education among the working class, universal suffrage, basic work safety provisions, the right to organize, and many other legal reforms that Marx defended at one point or another. Capitalists had numerous arguments against all of these things, and it was Marx who provided the rigorous counter-arguments the working class movement needed to know their reforms were economically viable. Thanks to a working class movement inspired by the theoretical and practical writings of Marx, we were able to overcome the worst excesses of 19th century Industrial capitalism.

One more thing that must be considered … Marx’s critique of capitalism applies as well as it did today as it did in the 19th century. Our economic system hasn’t substantively changed. Most of its changes are quantitative in nature, not qualitative, and the internal mechanics of the system. Instead of rejecting Marx’s thinking because of the fate of the Soviet Union, I would argue we better take up the mission of continuing to shorten the working day. Though Marx might have been mistaken in thinking that a shorter working day would usher in the “true realm of freedom” (at least, it hasn’t yet), it is inarguable that a shorter working day would benefit the workers of the world. When countries like China are suffering high youth unemployment, and when workers in America lack the time to socialize, it is perhaps a good time to consider a further reduction in the working day.

I often think about the difference between a “pompous catalogue of the ‘inalienable rights of man’” and the “modest Magna Charta of a legally limited working-day.” I suspect he meant not only the beginning of something as you note, but that we must look beneath the announced rhetoric to understand the nature of The Deal politics has produced. Marx almost gleefully catalogues how much the workers didn’t give af whether they allied with capitalists or aristocrats in pursuit of the reform they rightly saw as crucial.

Obviously, this kind of transactional approach can be and often is suggested in bad faith. But the meat of it is a good lesson.

I really love Chapter 10 of volume 1 and read it three times and wrote an essay on it for my DSA. They wouldn’t publish it because it was too long. I have been wanting to revise it since but haven’t found the time.